Mar 30, 2023

REDUCTIONS

Reductions or reduced speech is when an English speaker shortens or eliminates particular sounds. This can occur in the form of connected speech, reduced sounds, or contractions.

Reduction #1: To

You will almost always hear a native speaker reduce ‘to’ to /də/ or /tə/.

Though these words are quite short, native speakers like to reduce the sounds to smooth out their speech and ease the transition of sounds between words.

We often say /tə/ when ‘to’ follows a word that ends with a consonant.

/tə/: “Lina gave us a great presentation to think about.” In this case, ‘presentation’ ends with an ‘n’, so ‘to’ takes on the /tuh/ sound.

However, we also soften the sound to /də/ when ‘to’ follows a word ending with a vowel.

/də/: I need you to pick up the kids after work today. In this example, ‘you’ ends with a vowel sound, so we smooth our speech by following up with /də/.

It’s important to remember that dialects and personal speaking styles vary. One person may use the pronunciation /də/ more often than /tə/, and vice versa.

Reduction #2: Of

Similarly, when ‘of’ follows a word ending with a consonant, it’s often reduced to /ə/ tagged to the end of the word.

For example, you might hear a marketing manager say, “Mosta the engagement with our brand comes from Instagram.’

‘Mosta’ is a reduced form of the words ‘most’ and ‘of’.

Here are some other commonly reduced combinations with ‘of’:

Kind of = kinda

Sort of = sorta

Lots of = lotsa

A lot of = a lotta

Reduction #3: For & You

The third most common form of reduced speech is the modifications of ‘for’ to /fər/ and your/you’re to /yər/.

You may be noticing a pattern here. The reduction of ‘for’ and ‘your’ also use the /ə/ sound.

To clarify, imagine someone has asked you who a gift is for. You might reply with, “It’s for the hostess”. Notice how speaking at a natural speed smoothly reduces the word to /fər/?

Pro Tip: When ‘for’ or ‘your’ are pronounced in their reduced form, the /r/ sound links to the next word.

For example, you might ask a contractor, “Could you send your estimate for my roof by the end of the week?” The /r/ sound in ‘your’ carries over to the beginning of ‘estimate’ and ‘you’ is pronounced like /yə/.

Reduction #4: Contractions

Contractions of two words or more are a dime a dozen. Native speakers use contractions often and this also creates the illusion of speaking quickly.

Contractions are created in negative forms that include ‘not’.

For instance, we often hear someone say “I don’t like running” instead of “I do not like running”. When contracted, ‘not’ sounds omits the /o/ sound.

Moreover, we also contract the verb ‘will’ to say /ɪl/.

For example, you might tell a coworker, “I’ll get back to you by the end of the week”.

When ‘will’ combines with a pronoun, it elongates the vowel sound and attaches an /il/ sound to the end.

For instance:

I’ll sounds like /aɪl/

You’ll sounds like /yul/

He’ll sounds like /hil/

The same could also be said for the verb ‘had’ and modal ‘would’.

Native speakers contract both these words to a simple /d/ sound. This means you need to know the context surrounding the contraction to identify which word was used by the speaker.

Imagine a friend explains a last-minute change of plans by sharing, “I’d been on my way when I realized that I forgot to mail the letter”. Can you guess which word was reduced here?

The same process also applies to ‘would’ and ‘have’ when they are reduced to /d/.

Instead of “I would need to think about it”, you would say, “I’d need to think about it”.

That being said, the most common contractions in everyday English involve combining two words to create a completely new word.

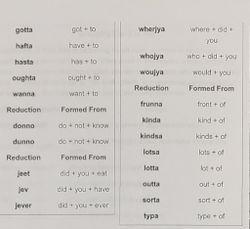

Native speakers contract ‘going’ and ‘to’ to say gonna,

I’m gonna need more time. When saying gonna, native speakers reduce the vowels ‘o’ and ‘a’ to an /uh/ sound.

‘Want’ and ‘to’ to say wanna,

They wanna do movie night on Friday. Like gonna, wanna reduces the /a/ sounds to /uh/.

‘Got’ and ‘to’ to say gotta,

I’ve gotta take my daughter to her recital. When ‘got’ and ‘to’ combine, they take on a softer /d/ sound – godda.

‘Give’ and ‘me’ to say gimme,

Please gimme a moment to collect my thoughts.

And ‘don’t’ and ‘know’ to say dunno

They dunno when the orders will arrive.

What is connected speech in English?

The first thing to understand about speaking English naturally is that it is very different from speaking English clearly.

In English, words bump into each other. We reduce words when we’re speaking, contract them, and then mash them together.

That’s what connected speech is: it’s continuous spoken language like you’d hear in a normal conversation. It’s called connected speech because the words are all connected, with sounds from one running into the next.

Examples of connected speech

1. Catenation or linking

Catenation happens when a consonant sound at the end of one word gets attached to the first vowel sound at the beginning of the following word.

For example, when native speakers say “an apple” you’ll usually hear them say, “anapple”. The “n” in “an” gets joined with the “a” sound in “apple” and it becomes almost like a single word.

In some cases, the sound of the consonant sound changes when it’s linked. For example, if I were to say “that orange” you would probably hear me change the final consonant “t” sound to a “d” sound as in “thadorange”.

Here are some other examples:

“trip over” often sounds like “tripover”

“hang out” often sounds like “hangout”

“clean up” often sounds like “cleanup”

2. Intrusion

Intrusion happens when an extra sound squishes in between two words. The intruding sound is often a “j”, “w”, or “r”.

For example, we often say:

“he asked” more like “heyasked”

“do it” more like “dewit”

“there is” more like “therris”

3. Elision

Elision happens when the last sound of a word disappears. This often happens with “t” and “d” sounds. For example:

“next door” often gets shortened to “nexdoor”

“most common” often gets shortened to “moscommon”

4. Assimilation

Assimilation happens when sounds blend together to make an entirely new sound. Some examples include:

“don’t you” getting blended into “don-chu”

“meet you” getting blended into “mee-chu”

“did you” getting blended into “di-djew”

5. Geminates

Geminates are a doubled or long consonant sound. In connected speech, when a first word ends with the same consonant sound that the next word begins with, we often put the sounds together and elongate them. For example:

“single ladies” turns into “single-adies”

“social life” turns into “social-ife”

Notice that in none of these cases does the spelling actually change. It’s just the sounds that change when we say them.

Is connected speech important?

Yes and no.

I actually like to think of learning connected speech in two halves: understanding it when you hear it, and recreating it when you’re speaking yourself.

Understanding connected speech when it’s used is extremely important. This is how native English speakers really talk. If you can’t understand English as it’s really spoken, you’re not really able to use the language.

So listening to connected speech and being able to parse it into meaning is very important.

Producing connected speech isn’t very important. Native speakers don’t need you to use connected speech to understand you. If you speak English clearly, carefully enunciating each syllable, you may sound a bit unnatural, but you’ll certainly be understood.

So being able to use connected speech yourself doesn’t have to be a priority.

Confusion about meaning in connected speech is especially common for non-native speakers listening to native speakers talk. Anyone learning a foreign language needs practice listening to it being spoken naturally, but learners of English have a difficult time picking out individual words from connected speech because words are so often slurred.

Native speakers take many verbal shortcuts in ordinary conversation that wouldn't be present in written English, and switching between written and spoken English takes getting used to when it isn't your first language.

You’ve probably noticed that English isn’t always pronounced the way it’s written. When we speak, the sounds in English sometimes change because we speak in streams of speech, not word by word. Here are two different pronunciations of the same question:

(Careful, word-by-word) Could you give me that book on accounting?

(Natural stream of speech) “Coujoogimmethabookonaccounting?”

1. How is it going? Wait, is everything ok?

2.Where is Adam? Did you see him leave?

3.Sara came and he got really mad at her.

4.I don’t know what his problem is, or maybe it’s her problem.

5. They have both had a hard time.

6. I don’t think he has been happy at his job.

7.I know she wants to quit hers.

8. Oh, did you get his text? They both had to leave, but I guess things are ok.

By undefined

23 notes ・ 223 views

English

Upper Intermediate