Sep 11, 2022

Poem

Stanza One

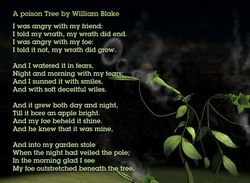

I was angry with my friend;

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

The poet is not only expressing his anger towards his friend as well as his foe in this stanza, but he has also depicted the difference between two types of anger. He states that when you are angry with a friend, you convince your heart to forgive him. Even though you are hurt and you know that he did injustice to you, you try your best to forget the past and end the feeling of vengeance in your heart.

On the other hand, when you are angry with an enemy, it takes ages for you to calm your anger. Yet, the anger and the feeling of vengeance do not diminish, even with time. In fact, the vengeance simply grows.

Stanza Two

And I watered it in fears,

Night & morning with my tears:

And I sunned it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles.

The poet is making a confession in this stanza of ‘A Poison Tree’ – it is he, who is solely responsible for the hatred that has grown in his heart for his enemy. It is he, who has increased the vengeance in his heart. He has nurtured the hatred with his fears, spending hours together, crying for the ill that has been caused to him by his enemy.

He has also nurtured the hatred with his sarcastic smiles, imagining ill and cursing his enemy to go through the same or worse sufferings that he has been through.

Stanza Three

And it grew both day and night,

Till it bore an apple bright.

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine.

The poet states that it is because of his dwelling in the same hatred, that it has grown every day. The hatred gave birth to an apple. The fruit signifies the evil that has taken birth in the heart of the poet. He states that he has now come to a point from where he can’t turn back and forget about his enemy until he does something to soothe his vengeance.

Finally, the day comes when the poet’s enemy has met the evil fruit of vengeance, that he has grown with his fears, tears, and sarcasm. The fruit has now turned into a weapon. When the enemy confronts this anger, it is time for the weapon to serve the purpose that it has been made for.

Stanza Four

And into my garden stole.

When the night had veiled the pole;

In the morning glad I see,

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

And, so the poet states, the very next morning, the purpose is served. When the poet wakes up and glimpses in the garden, he sees something that relaxes his mind and calms his vengeance forever. The darkness of the night acted as an invisible cloak for the poet. Now, it is a beautiful morning.

There he is; his enemy, dead under the tree of his hatred. He bit the poisoned apple of his vengeance. He is murdered.

Personal Commentary

Anger is one of the most aggressive emotions that we all possess as humans. And why only humans, this emotion is possessed by all the living beings; even the animals are seen fighting with rage and anger on the streets and in the woods.

In ‘A Poison Tree,’ the poet has clearly stated his anger and feeling of vengeance in his heart. He has forgiven his friend, but he hasn’t and will never forgive his enemy for the wrongs that he has done and the hurt he has caused to him. He remembers every little thing that he has wrongly done to put him down and hurt him terribly.

The poet clearly says that he has himself not forgiven his enemy, even though he could. He has made sure that he doesn’t forget all the wrongs that he has been done because he has suffered enough due to his foe. At first, he may have tried to forget about all that has been caused to him, but with the growing time, the hatred in his heart developed and he kept dwelling in the same vengeance.

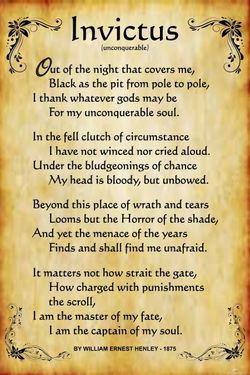

“Invictus” Summary

The speaker begins by emerging from a metaphorical night that lies on top of the speaker like a physical thing. This night, which seems to fill the whole world, is as dark as Hell. Despite this darkness, the speaker feels gratitude towards any god or gods that may exist for granting unshakeable resilience.

Looking back on life's past challenges, which constrained the speaker like a giant fist, the speaker remembers never showing discomfort or complaining. Going even further, the speaker compares life's unexpected mishaps to being beaten with a heavy implement. The speaker was damaged by this beating, yet that fact did not decrease the speaker's pride or resolve.

Now the speaker looks beyond the present of anger and sadness to the future. Unfortunately, the future's only certainty is death, which hangs over the present like a terrifying shadow. However, the speaker once again affirms that the threat of inevitable suffering does not, and never will, frighten the speaker.

The speaker doesn't care how challenging life becomes, alluding to a biblical passage in which a narrow gate represents extreme difficulty. Nor does the speaker care how many horrible events lie in the book of fate. The speaker controls the course of their own inner life. Like a ship's captain, the speaker remains in charge of their inner life's unconquerable element: the soul.

“Invictus” Themes

Theme Suffering and Resilience

Suffering and Resilience

“Invictus” is above all a poem about resilience in the face of suffering. This resilience comes from the courage to embrace life and refuse despair. In addition to its proud statement of the speaker’s current bravery, the poem is also a balm against any future instances of adversity; it’s ultimately an assertion of the boundless strength of the human spirit.

The poem has a repetitive structure that emphasizes the recurring nature of adversity and the constancy of inner strength. Note how each stanza opens with a description of adversity and ends with an affirmation of emotional fortitude. The first stanza, for instance, begins with the prepositional phrase “out of” as the speaker emerges from the darkness of suffering that “covers” the speaker. This stanza then closes with an assertion of the speaker's "unconquerable soul.” That is, the speaker’s resilience remains untouched by life’s difficulties.

The second stanza takes a similar form, now turning to physical bludgeoning as a metaphor for life’s unpredictable difficulties. Though “bloodied,” the speaker doesn't bow to these difficulties and instead faces them head on. The third and fourth stanzas consider future challenges that lie “Beyond this place," but again reaffirm that the speaker remains “unafraid” and self-possessed as “the master of my fate.”

Not only does the speaker emphasize personal strength in the face of hardship, but the poem specifically refuses to complain about life's seemingly relentless adversities. Despite all that the speaker has faced, this person has “not winced nor cried aloud.” The poem doesn't whine or languish in sadness, but rather states the speaker’s philosophy in an assertive manner meant to rouse and inspire. This is especially clear in the poem's famous last two lines. Here, the speaker takes on the authority of “master” and “captain,” as well as the pride and glory associated with these terms. This use of “captain” also ties into the title of the poem ("invictus" means "unconquerable") as a word related to the military, creating an aura of military valor. That is, the poem acts like a rallying cry made to inspire oneself, rather than as a lamentation about the difficulties of life.

Though the poem speaks proudly of past and present adversity, it also declares that all future challenges will be met with the same resilience. It this way, the poem articulates the speaker’s belief in a lifelong philosophy of courage. Note first how the poem almost always speaks in the present tense. In doing so, it affirms the vivacity and presence of the speaker, who has not given up on life: “My head is bloodied, but unbowed.” Yet As long as death “looms” in the future, there will always be challenges. And indeed, the second half of the poem asserts courage against “the menace of the years,” or future difficulties.

In the third stanza, the speaker notably uses the future tense to claim power over the future, saying the years “shall find me unafraid.” Here, the poem’s only use of a non-present tense emphasizes how the speaker’s strength won’t be diminished over time. Finally, in the fourth stanza, after speculating on what lies in store, the poem ends on a final anaphora of “I am” that reiterates the speaker's resolve. This “am” treats that resolve as a stable part of the speaker’s identity. Having given repeated affirmations of resilience, the speaker remains unshaken by past and future, knowing that inner courage will always serve as a fortification against trouble.

Theme Free Will Vs. Fate

Free Will Vs. Fate

The speaker’s pride in persevering through difficult times pits free will against fate. Free will is the idea that people can choose their own actions and thoughts, rather than being controlled by fate. Though the opposing ideas of free will and fate conflict throughout the poem, the speaker ultimately insists upon a middle ground, in which individuals freely choose their emotional responses to life’s inevitable constraints.

The challenges that the speaker describes don't come from specific sources, like people or even identifiable events. Rather, the poem depicts an individual person caught within vast and abstract sources of suffering. Note how the poem begins with images of “night” in the first line and “the pit,” or Hell, in the second. As metaphors, these two lines treat personal suffering as vague and cosmic in scope. This night of suffering covers the speaker, acting as a limitation, and is the first suggestion of fate—or inevitable hardship beyond the speaker's control—in the poem.

Next, “the fell clutch of circumstance” makes a blatant statement of fate as the poem’s central conflict. Again, as with “covers” in the previous stanza, “clutch” treats the individual speaker as a person caught within broad, vague difficulties. Here, circumstance has become vaguely personified as a malicious god that has the speaker within its grip, both echoing and contrasting with the benevolent “whatever gods may be” from the previous stanza. Finally, death—the last “punishment” on the “scroll” of fate—always looms as a certainty. It lies “Beyond this place of wrath and tears” as the “Horror of the shade.” Essentially, the speaker can’t expect anything from life beyond an eventual death; fate isn’t obligated to dole out happiness.

Yet, despite such facts as the certainty of death, the speaker believes in the ability to control one’s response to adversity. This in turn leads to a sense of inner freedom even as the speaker can't control things like "the fell clutch of circumstance" nor the "bludgeonings of chance." When the speaker says, “I have not winced nor cried aloud,” and “My head is bloody, but unbowed,” this emphasizes the temptation of doing exactly those things: wincing, crying out, bowing one’s head. The speaker makes a conscious choice not to do those things.

The final usage of “master” and “captain” again gestures at the idea of freedom. We define masters and captains by their ability—and responsibility—to choose. Yet the full phrases “master of my fate” and “captain of my soul” create some ambiguity. Up until now, the word “fate” was implied in words like “circumstance” as a cosmic force for suffering and death. How can the speaker control fate, after spending the whole poem describing the impossibility of doing so? The phrase “captain of my soul” helps point us in a new direction by seeing fate in terms of the speaker’s internal life. One can choose what happens within one’s own mind and in that way control the “fate” of one’s emotional life.

“Invictus” doesn’t find clear answers to the nature of fate or the possibility of acting freely. It does, however, assert that we all have mastery over own interior lives, which provides resilience against whatever forces seek to control us.

Theme Agnosticism

Agnosticism

“Invictus” places the speaker’s reponse to adversity within the context of God’s uncertain existence. This uncertainty about God, a view known as agnosticism, contrasts with the speaker’s faith in self-empowerment.

The first stanza uses both the words “gods” and “soul,” immediately suggesting that the speaker wants to, in some way, engage with religion. Yet each engagement comes with uncertainty. For instance, rather than saying “God,” as would a traditionally Christian speaker in this context, the speaker says “whatever gods may be.” Not only does this throw God’s existence into doubt, it also raises the possibility of other non-Christian divinities. Were the speaker to say instead, “I thank God / For my unconquerable soul,” we might have classified this poem, at least at the beginning, as a prayer or a devotional poem. That said, even as it is, the poem retains some aura of prayer.

In contrast to evoking divine goodness, this first stanza also has the religious imagery of Hell—“the pit.” The darkness of night and Hell represents the difficulty of understanding the forces that cause one’s suffering. As the speaker emerges “Out of” this darkness, it is not God that becomes clear, but the speaker’s own inner strength. This would ultimately suggest a rejection of religion as a source of guidance and fortitude in the face of suffering.

Further engaging with Christianity, the poem contains a biblical allusion in its final stanza. The phrase “strait the gate” comes from Matthew 7:14 in the King James Bible: “Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.” This quote more specifically comes from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, where he details the rigors of living a virtuous Christian life. Here, however, the speaker treats that difficulty not as an eventual good, but as another evil presented by fate—another potential hardship to overcome. Thus, Christianity deeply informs the poem while the speaker remains skeptical of it.

On the other hand, the speaker’s use of the word “soul” suggests a bolder and less uncertain attitude. The speaker professes unshakeable faith in the soul. However, the poem still leaves us with a limited vision of what that word actually means. After passing through spiritual uncertainty in the first three lines, the speaker lands on the “unconquerable soul.” In contrast to the “pit” of suffering, the soul becomes a core of strength, that which chooses life over despair. Yet, unlike Christianity, the poem does not assure us of the soul’s immortality. The “Horror” of death, which always "looms" over the speaker, offers no such promises.

At the end of the poem the soul remains uncorrupted. Yet now the speaker has become the soul’s “captain,” not simply relying on it but also in charge of it. This shift, though subtle, is still a shift. On one hand, it raises the poem’s valorous tone to an even greater intensity. On the other hand, this shift creates ambiguity about the nature of the soul. If you can “captain” your soul, that means you are also somehow separate from it. Rather than making choices, the soul becomes passive at the end of the poem; now, the speaker makes choices for the soul. So while the speaker retains faith in the soul, the soul’s exact nature remains unclear.

“Invictus” thus invokes Christian ideas of fate and suffering while refusing to commit to Christianity. The poem even subtly increases uncertainty about the nature of inner strength and the soul. Its faith in that strength, however, never wavers.

By undefined

5 notes ・ 10 views

English

Beginner