Apr 15, 2024

English: Morphology

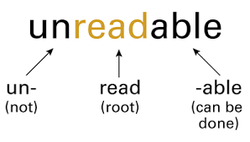

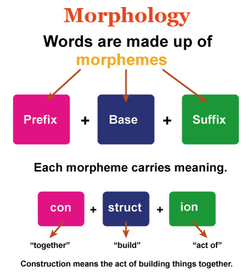

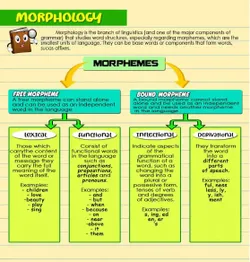

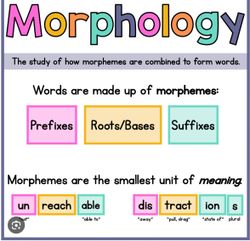

1. In linguistics, morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language. Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning

History: The word morphology is a Greek word made with a combination of two words, "morph"( means shape) + "ology"( study of the topic). This term was discovered by August Schleicher in 1859.

2. Morphology:

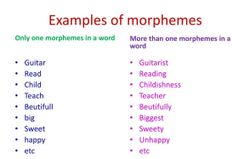

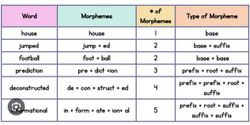

In language, words play an important role therefore, their study is mandatory. The study of words is termed morphology, which includes the formation of words and their relationship with other words in the same language. It details the structure of words (root words, suffixes, prefixes, stems, and parts of words). It is a part of linguistic (word) semantics and makes you investigate the construction of words in the language.

3. In English, a single letter can alter one-word pronunciation and meaning. For example: accept, accept, and expect. Sometimes, only pronunciation remains the same, and one letter difference changes the meaning.

Children start learning with the smallest sound, called "phonemes," ( pho·neme /ˈfōˌnēm/ ) and the smallest written sound, called "graphemes," but in reality, they start understanding words with morphemes (smallest unit of meaning like root word, an affix, one part of a compound word and so on). "Morphemes" is the minimal unit of words whose meaning cannot be subdivided further, and the study of these words is called "morphology."

4. "In language, the study of the smallest segment of language having some meaning called as morphology .

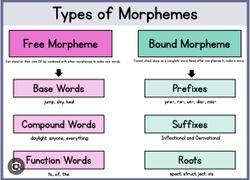

a. Free morphemes - These words occur alone, like "bad" words occur alone-other examples like picture, father, adverse, gentle, gem, worse, etc.

b. Bound morphemes - These words occur with another morpheme like "ly," which is a bound morpheme that has its meaning but can't stand alone. It always attaches as a suffix to other morpheme and gives it a meaning.

Bad + ly = Badly

Bound morphemes have two categories: derivational morpheme and inflectional morpheme.

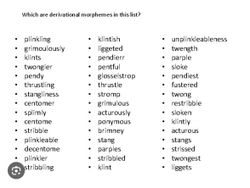

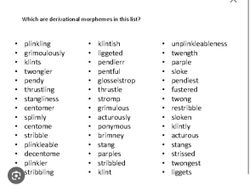

5. Derivational morphemes:

These are morphemes that can change the grammatical category of the root word. For example: adverse + ly = adversely.

Inflectional morpheme:

They can alter the word but don't change the root word's grammatical category. For example: Cat + s = cats

Morphology definition

Words are divided into function words (grammatical) and lexical words (content).

6. Lexical words include verbs, nouns, adverbs, and adjectives and are called open-class words. These carry the content or meaning of a message.

For example: deliver, meet, stand, compact, tree, excess, blanket, etc. Lexical words or morphemes are important to the sentence as after their deletion, the sentence loose it's meaning.

Function words (functional morphemes) are considered articles, prepositions, conjunctions, and pronouns and are known as closed-class words because no new word is hardly or is rarely added to this class. They don't carry the content of a message but are more functional and meaning full or coordinate the meaningful words. For example: there, we, and, so, if, with, etc.

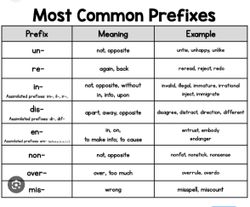

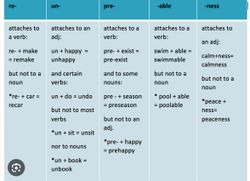

7. Prefix, suffix, infix, and circumfix are added to morphemes like re, or, um, gr, or t that adds meaning to a word.

Purpose of morphology

The main aim of morphology is the deep understanding of morphemes in teaching and learning because these are important for phonics (reading and spelling), vocabulary, and comprehension.

Lesson: Morphology

Terms

Morphology Study of morphemes and the

internal construction of words. Morphology

includes the grammatical processes of

bound morphemes by modifying the root

word.

Morpheme Smallest units of meaning in a

language.

Free morpheme (unbound morpheme)

Morpheme that can stand alone.

Bound Morpheme Word that is created

when affixes are used to modify the root

word. The process of these bound

morphemes are divided in two types of

words, inflectional and derivational.

To spot a word that has an inflection or

derivation, we must spot something called an

affix.

Root Basic word to which affixes are

added, the root word itself can also be an

independent word.

Affix Additional element placed at the

beginning or end of a root, stem, or word, or

in the body of a word, to modify its meaning.

Inflection Change in the form of a free

morpheme to mark such distinctions as

tense, person, number, gender, mood,

voice, and case.

Deveration Adding affixes to a free

morpheme that creates a different definition

for the word.

English has two main types of affixes:

prefix and suffix.

Prefix Letter or a group of letters that

appears at the beginning of a word and

changes the original meaning.

(Note: All English prefixes are deverational,

there are no English inflectional prefix words)

Suffix Letter or group of letters placed at

the end of a word to create a new word

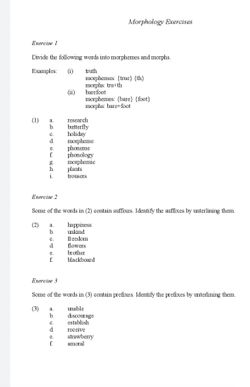

Linguistics: Topic 7 Morphology

Choose the following words, identify the individual morphemes, stating whether they are root (R),

inflectional (I) or derivational (D). Give the root in its most usual form (the form it occurs in when

uninflected, or the form you would look up in a dictionary).

1. Friendliness

2. Unhappier

3. Childishly

4. Purifying

5. Clinician

6. Zoologist

7. Bookmaker’s

8. Impracticalities

9. Impressions

10. Resignation (difficult!)

1. Friendliness = friend (R) + ly (D noun→adjective) + ness (D adjective→noun ‘the quality

of being an N)

2. Unhappier = un (D ‘opposite’) + happy (R) + er (I ‘more’)

3. Childishly = child (R) + ish (D noun→adjective ‘like a N’) + ly (D adjective→adverb)

4. Purifying = pure (R) + ify (D adjective→verb ‘to make A’) + ing (I, present participle)

5. Clinician = clinic (R) + ian (D ‘person who does N’) Actually ‘clinic’ comes from the Greek

meaning ‘bedside’ where ‘bed’ is kline, so it is a D in Greek. But an English speaker would

not be expected to know this.

6. Zoologist = zoo (bound R ‘life’) + (o)logy (bound R ‘study’) + ist (D ‘person doing N’)

7. Bookmaker’s = book (R) + make (R) + er (D verb→noun ‘person who does V’) + ‘s (I

‘possessive’). Worth noting that this is a special meaning of ‘make a book’!

8. Impracticalities = in (D ‘negative’) practice (R) + al (D noun→adjective) + ity (D

adjective→noun) + s (I ‘plural’)

9. Impressiveness = in (D ‘inwards’) + press (R) + ive (D verb→adjective) + ness (D

adjective→noun ‘quality of being A’)

10. Resignation = ? re (D usually means ‘again’ but here means ‘to undo’, so perhaps ‘resign’

is the root?) + sign (R) + ation (D verb→noun ‘act of V-ing’) … Alternatively ate (‘cause

to V) + ion (D verb→noun ‘act of V-ing’)

Words

What’s a word? It seems almost silly to ask such a simple question, but if you think about it, the question doesn’t have an obvious answer. A famous linguist named Ferdinand de Saussure said that a word is like a coin because it has two sides to it that can never be separated. One side of this metaphorical coin is the form of a word: the sounds (or letters) that combine to make the spoken or written word. The other side of the coin is the meaning of the word: the image or concept we have in our mind when we use the word. So a word is something that links a given form with a given meaning.

2. Words are Free

Linguists have also noticed that words behave in a way that other elements of mental grammar don’t because words are free. What does it mean for a word to be free? One observation that leads us to say that words are free is that they can appear in isolation, on their own. In ordinary conversation, we don’t often utter just a single word, but there are plenty of contexts in which a single word is indeed an entire utterance. Here are some examples:

What are you doing? Cooking.

What are you cooking? Soup.

How does it taste? Delicious.

Can I have some? No.

Each of those single words is perfectly grammatical standing in isolation as the answer to a question.

3. Words are Moveable

Another reason we say that words are free is that they’re moveable: they can occupy a whole variety of different positions in a sentence. Look at these examples:

Penny is making soup.

Soup is delicious.

I love to eat soup when it’s cold outside.

The word soup can appear as the last word in a sentence, as the first word, or in the middle of a sentence. It’s free to be moved around.

4. Words are Inseparable

The other important observation we can make about words is that they’re inseparable: We can’t break them up by putting other pieces inside them. For example, in the sentence,

Penny cooked some carrots.

The word carrot has a bit of information added to the end of it to show that there’s more than one carrot. But that bit of information can’t go just anywhere: it can’t interrupt the word carrot:

*Penny cooked some car-s-rot.

This might seem like a trivial observation – of course, you can’t break words up into bits! – but if we look at a word that’s a little more complex than carrots we see that it’s an important insight. What about:

Penny bought two vegetable peelers.

That’s fine, but it’s totally impossible to say:

*Penny bought two vegetables peeler.

Even though she probably uses the peeler to peel multiple vegetables. It’s not that a plural -s can’t go on the end of the word vegetable; it’s that the word vegetable peeler is a single word (even though we spell it with a space between the two parts of it). And because it’s a single word, it’s inseparable, so we can’t add anything else into the middle of it.

5. Morphemes

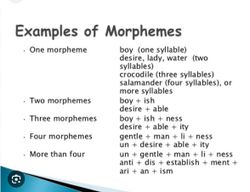

So we’ve seen that a word is a free form that has a meaning. But you’ve probably already noticed that there are other forms that have meaning and some of them seem to be smaller than whole words. A morpheme is the smallest form that has meaning. Some morphemes are free: they can appear in isolation. (This means that some words are also morphemes.) But some morphemes can only ever appear when they’re attached to something else; these are called bound morphemes.

Bound Morphemes

Let’s go back to that simple sentence,

Penny cooked some carrots.

It’s quite straightforward to say that this sentence has four words in it. We can make the observations we just discussed above to check for isolation, moveability, and inseparability to provide evidence that each of Penny, cooked, some, and carrots is a word. But there are more than four units of meaning in the sentence.

Penny cook-ed some carrot-s.

6. The word cooked is made up of the word cook plus another small form that tells us that the cooking happened in the past. And the word carrots is made up of carrot plus a bit that tells us that there’s more than one carrot.

That little bit that’s spelled –ed (and pronounced a few different ways depending on the environment) has a consistent meaning in English: past tense. We can easily think of several other examples where that form has that meaning, like walked, baked, cleaned, kicked, kissed.

This –ed unit appears consistently in this form and consistently has this meaning, but it never appears in isolation: it’s always attached at the end of a word. It’s a bound morpheme.

For example, if someone tells you, “I need you to walk the dog,” it’s not grammatical to answer “-ed” to indicate that you already walked the dog.

Likewise, the bit that’s spelled –s or –es (and pronounced a few different ways) has a consistent meaning in many different words, like carrots, bananas, books, skates, cars, dishes, and many others. Like –ed, it is not free: it can’t appear in isolation. It’s a bound morpheme too.

7. Simple vs Complex Morphemes

If a word is made up of just one morpheme, like banana, swim, hungry, then we say that it’s morphologically simple, or monomorphemic.

But many words have more than one morpheme in them: they’re morphologically complex or polymorphemic. In English, polymorphemic words are usually made up of a root plus one or more affixes.

The root morpheme is the single morpheme that determines the core meaning of the word. In most cases in English, the root is a morpheme that could be free. The affixes are bound morphemes.

English has affixes that attach to the end of a root; these are called suffixes, like in books, teaching, happier, hopeful, singer. And English also has affixes that attach to the beginning of a word, called prefixes, like in unzip, reheat, disagree, impossible.

8. Infixes

Some languages have bound morphemes that go into the middle of a word; these are called infixes. Here are some examples from Tagalog (a language with about 24 million speakers, most of them in the Philippines).

[takbuh] run [tumakbuh] ran

[lakad] walk [lumakad] walked

[bili] buy [bumili] bought

[kain] eat [kumain] ate

It might seem like the existence of infixes is a problem for our claim above that words are inseparable. But languages that allow infixation do so in a systematic way — the infix can’t be dropped just anywhere in the word. In Tagalog, the position of the infix depends on the organization of the syllables in the word.

Did you spot the difference between present tense and past tense? The past tense of the word contains the infix, “um,” immediately following the first letter of the word.

9. Inflectional Morphology

Inflectional morphemes are morphemes that add grammatical information to a word. When a word is inflected, it still retains its core meaning, and its category stays the same. We’ve actually already talked about several different inflectional morphemes:

Noun Number

The number on a noun is inflectional morphology. For most English nouns the inflectional morpheme for the plural is an –s or –es (e.g., books, cars, dishes) that gets added to the singular form of the noun, but there are also a few words with irregular plural morphemes. Some languages also have a special morpheme for the dual number, to indicate exactly two of something. Here’s an example from Manam, one of the many languages spoken in Papua New Guinea. You can see that there’s a morpheme on the noun woman that indicates dual, for exactly two women, and a different morpheme for plural, that is, more than two women.

Manam (Papua New Guinea)

/áine ŋara/ that woman singular

/áine ŋaradiaru/ those two women dual

/áine ŋaradi/ those women plural

10. Verb Tense

The tense on a verb is also inflectional morphology. For many English verbs, the past tense is spelled with an –ed, (walked, cooked, climbed) but there are also many English verbs where the tense inflection is indicated with a change in the vowel of the verb (sang, wrote, ate). English does not have a bound morpheme that indicates future tense, but many languages do.

Verb Agreement

Another kind of inflectional morphology is agreement on verbs. If you’ve learned French or Spanish or Italian, you know that the suffix at the end of a verb changes depending on who the subject of the verb is. That’s agreement inflection. Here are some examples from French. You can see that there’s a different morpheme on the end of each verb depending on who’s doing the singing.

French

1st je chante I sing

2d tu chantes you sing

3d elle chante she sings

1st nous chantons we sing

2d vous chantez you (pl.) sing

3d elles chantent they sing

11. Case Inflection

And in some languages, the morphology on a noun changes depending on the noun’s role in a sentence; this is called case inflection.

Take a look at these two sentences in German: The first one, Der Junge sieht Sofia, means that, “The boy sees Sofia”. Look at the form of the phrase, the boy, “der Junge”. Now, look at this other sentence, Sofia sieht den Jungen, which means that “Sofia sees the boy”. In the first sentence, the boy is doing the seeing, but in the second, the boy is getting seen, and the word for boy, Junge has a different morpheme on it to indicate its different role in the sentence. That’s an example of case morphology, which is another kind of inflection.

Derivational Morphology

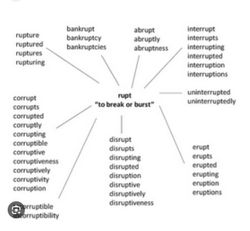

The other big job that morphemes have is a derivation. The derivation is the process of creating a new word. The new, derived word is related to the original word, but it has some new component of meaning to it, and often it belongs to a new category.

12. One of the most common ways that English derives new words is by affixing a derivational morpheme to a base. For example, if we start with a verb that describes an action, like teach, and we add the morpheme –er, we derive a morphologically complex noun, teacher, that refers to the person who does the action of teaching. That same -er morpheme does the same job in singer, dancer, baker, and writer.

Verb Suffix Noun

teach -er teacher

sing -er singer

dance -er dancer

bake -er baker

write -er writer

13. we start with an adjective like happy and add the suffix –ness, we derive the noun that refers to the state of being that adjective, happiness.

Verb Suffix Noun

teach -er teacher

sing -er singer

dance -er dancer

bake -er baker

write -er writer

Adding the suffix –ful to a noun derives an adjective, like hopeful.

Noun Suffix Adjective

hope -ful hopeful

joy -ful joyful

care -ful careful

dread -ful dreadful

Adding the suffix–ize to an adjective like final derives a verb like finalize.

Adjective Suffix Verb

final -ize finalize

modern -ize modernize

social -ize socialize

public -ize publicize

Notice that each of the morphologically complex derived words is related in meaning to the base, but it has a new meaning of its own. English also derives new words by prefixing, and while adding a derivational prefix does lead to a new word with a new meaning, it often doesn’t lead to a category change.

Prefix Verb Verb

re- write rewrite

re- read reread

re- examine reexamine

re- assess reassess

14. Each instance of derivation creates a new word, and that new word could then serve as the base for another instance of derivation, so it’s possible to have words that are quite complex morphologically.

For example, say you have a machine that you use to compute things; you might call it a computer (compute + -er).Then if people start using that machine to perform a task, you could say that they’re going to computerize (computer + -ize) that task. Perhaps the computerization (computerize + -ation) of that task makes it much more efficient. You can see how many words have many steps in their derivations.

An interesting thing to note is that once a base has been inflected, then it can no longer go through any derivations. We can inflect the word computer so that we can talk about plural computers, but then we can’t do derivation on the plural form (*computers-ize). Likewise, we can add tense inflection to the verb computerize and talk about how yesterday we computerized something, but then we can’t take that inflected form and use it as the base for a new derivation (*computerized-ation). Inflection always occurs as the last step in word formation.

By undefined

37 notes ・ 2 views

English

Intermediate