Dec 23, 2024

CH9: Feel Good Productivity

[P1]

𝘾𝙃𝘼𝙋𝙏𝙀𝙍 𝟵 : 𝘼𝙇𝙄𝙂𝙉

The Pacific Crest Trail is not for the faint of heart. Spanning 2,650 miles of mountainous terrain in the western United States, it encompasses the entire length of America, from the deserts at the Mexican border to the mountains of north Washington. It’s renowned as one of the most arduous – and sometimes dangerous – hiking trails in America.

Every summer, thousands of intrepid walkers set off on the trail, beginning in spring and knowing they won’t arrive at the Canadian border until five months later. For most people, this sounds like a hellish feat of endurance. For University of Missouri professor Kennon Sheldon, it sounded like a perfect opportunity for a psychological experiment.

Sheldon is a titanic figure in a recent wave of research into human motivation. At the turn of the millennium, many people thought that the great questions about motivation had been resolved.

As we learned in Part 1, since the 1970s scientists had been aware of the two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is where you’re doing something because it feels inherently enjoyable.

Extrinsic motivation is where you’re doing something because of an external reward – like making money, or winning a prize. In the years since these two forms of motivation were theorised, countless studies had shown that when we’re intrinsically motivated to do something, we’re more effective and energised by doing it; and that extrinsic rewards can, in the long run, make us less motivated to do something for its own sake. Intrinsic motivation = good, extrinsic = bad. And that was that.

[P2]

Except Sheldon had a hunch that things might be a bit more complicated. Starting in the 1990s, he started to wonder whether we were missing something crucial about the science of motivation. Yes, on the face of it, the evidence seemed clear that extrinsic motivation was ‘worse’ than intrinsic motivation. At the same time, though, our lives are filled with instances in which we clearly are motivated by extrinsic rewards – and motivated well.

Imagine a student (let’s call her Katniss) studying for exams. Katniss doesn’t enjoy the studying process itself, so her motivation to study isn’t intrinsic. For now, she’s motivated by something other than the pure joy of studying and learning.

How might Katniss be motivating herself to study? Here are some options:

• 𝑶𝒑𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏 𝑨 I’m studying because my parents are forcing me to. I hate this subject, but if I don’t pass, I’ll be grounded for a month. I need to study to avoid this terrible punishment.

• 𝑶𝒑𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏 𝑩:I’m studying out of a sense of guilt. I hate this subject, but I know that my parents have worked hard to send me to this school, and I know I should value the opportunity to do well so that I can get into a good college. I feel anxious and guilty when I’m not studying, so I’m putting in a few hours of work each night for this exam.

• 𝑶𝒑𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏 𝑪: I’m studying because I genuinely care about doing well in school. Yes I hate this subject, but I have to pass this exam to qualify for the classes I actually want to take next year. And I’m trying to do well in those because I really want to go to college, to broaden my horizons, and maybe even apply to medical school someday. My parents aren’t forcing me to do any of this. Yes they’ll be disappointed if I fail, but I’m not studying for them. I’m studying for me.

All three of these options would fall under the category of ‘extrinsic motivation’: in each case, Katniss isn’t studying because it’s inherently enjoyable. Instead, she’s studying to achieve some external outcome (avoiding punishment, eliminating guilt, or getting

into her desired classes). But clearly, these three options represent very different attitudes towards work and life. Option C might even be quite a healthy form of motivation: one that encourages Katniss to work towards goals she values, even if the process isn’t intrinsically pleasurable.

Katniss’ example demonstrates that, in fact, not all extrinsic motivation is inherently ‘bad’. Like Katniss studying for the subject she hates, we all have to do things we don’t enjoy at times. And even when we start off enjoying something, if we do it for long enough, there are always going to be periods of hardship. In these moments, it’s rarely helpful to be told that if only we were enjoying ourselves more we’d be able to persevere.

[P3]

⚙️ 𝙉𝙤𝙩 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙚𝙭𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙞𝙘 𝙢𝙤𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙞𝙨 𝙞𝙣𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙡𝙮 ‘𝙗𝙖𝙙’.

Which brings us back to Sheldon and the Pacific Crest Trail. He began to suspect that anyone who embarked on the PCT was pretty likely to experience a collapse in intrinsic motivation at some point. What was motivating them to continue? he wondered.

So he decided to test it out. In 2018, Sheldon recruited a group of people who were interested in hiking the PCT. This group represented a mix of abilities. Seven had never backpacked before; thirty-seven had backpacked ‘a few times’; forty-six had backpacked ‘quite a lot’; and four had done it all their life. Before the hike started, Sheldon measured their motivation by getting participants to rate the accuracy of the following statements, each measuring a different type of motivation:

‘I’m hiking the PCT because…’

• hiking the PCT will be interesting

• hiking the PCT is personally important to me.

• I want to feel proud of myself.

• I will feel like a failure if I didn’t hike the PCT.

• Important people will like me better if I complete the PCT.

• Honestly, I don’t know why I am hiking the PCT.

[P4]

When Sheldon looked at the data, he found that practically all the hikers saw drops in intrinsic motivation during the marathon hike. This isn’t surprising – when you’re walking 2,650 miles across freezing terrain over five months, it’s hard to genuinely enjoy every step.

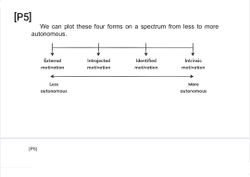

Sheldon was more interested in the form of extrinsic motivation the hikers turned to when their intrinsic motivation inevitably declined. By 2017, many scientists had begun to suspect that, as with Katniss studying for her exams, there were three discrete types of extrinsic motivation in addition to the purely intrinsic form. They fall on a spectrum called the ‘relative autonomy continuum’ (or RAC):

• 𝐄𝐱𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐌𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. ‘I’m doing this because important people will like and respect me more if I do.’ People who highly rated this statement have high external motivation.

• 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐌𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. ‘I’m doing this because I’ll feel guilty or bad about myself if I don’t.’ People who highly rated this statement have high introjected motivation.

• 𝐈𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐌𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. ‘I’m doing this because I truly value the goal it’s helping me work towards.’ People who highly rated this statement have high identified motivation.

• 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐜 𝐌𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. ‘I’m doing this because I love the process as an end in itself.’ People who highly rated this statement have high intrinsic motivation.

[P6[

External motivation is the form of extrinsic motivation that’s the least autonomous; instead of us being motivated by any kind of internal force, we’re being controlled by the opinions, rules and rewards offered by others. Further along the spectrum, identified motivation is the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation. Even though we might be doing something for the external reward associated with it, we value that reward or end-goal – and crucially, that value was determined by us, not foisted upon us by others.

Using this framework, Sheldon spotted something fascinating about the PCT hikers. The best predictor of their performance was the specific kind of extrinsic motivation they drew upon when their intrinsic motivation waned. Using the data he collected on the hikers’ motivation, wellbeing and hike performance, he showed that those who had higher levels of both introjected and identified motivation were far more likely to complete the trail. They managed to tap into these forms of extrinsic motivation to help sustain their progress even when the going got tough.

At the same time, Sheldon asked each of the walkers about their mood on the hike, using a series of well-established tests for subjective well-being (SWB), psychology jargon for ‘happiness’. Therein lay his second intriguing insight: the only type of extrinsic motivation that corresponded with greater happiness was identified motivation. In other words, it was the hikers who motivated themselves by aligning their actions with what they truly valued who not only completed the trail – but also felt happiest at the end of it. Sheldon didn’t use the term, but you might say that these hikers were experiencing feel-good productivity.

This study hints at our final insight into reducing our risk of burnout. So far, we’ve explored how to avoid what I call overexertion burnouts, which arise from taking on too much, and depletion burnouts, which arise from working too hard. But there’s a third kind of burnout: one I call misalignment burnout.

Misalignment burnout arises from the negative feelings that arise when our goals don’t match up to our sense of self. We feel worse – and so achieve less – because we’re not acting authentically. In these moments, our behaviour is driven by external forces – rather

than by a deeper alignment between who we are and what we’re doing. This alignment is something that only intrinsic and identified motivation can offer.

The solution? To work out what really matters to you – and align your behaviour with it.

It’s a transformative method; one that can make us feel fundamentally better about our lives. We’ve already explored that we all have to do things we don’t like, and that others expect of us. I don’t particularly enjoy taking my car to get serviced, or cleaning the toilet, or filing my taxes. In these moments, we might not enjoy the task we’re undertaking – and that can drain our energy. But we can sustain our feel-good productivity by aligning our present-day actions with a deeper sense of self.

[P7]

𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗟𝗢𝗡𝗚-𝗧𝗘𝗥𝗠 𝗛𝗢𝗥𝗜𝗭𝗢𝗡

When it comes to aligning your actions with your values, it can be helpful to think about the long term. The really long term.

Consider as an example the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake. On 17 January 1994, a 6.7 magnitude earthquake shook the city – killing fifty-seven people and injuring thousands more. Among the survivors were the employees of Sepulveda Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC), located just 2km from the epicentre. The hospital was severely damaged and many of the hospital employees’ homes were also destroyed.

A group of researchers led by Professor Emily Lykins at the University of Kentucky used this harrowing experience to explore a simple concept: that when we think about death, we get a clearer view of life.

[P8]

⚙️ 𝙒𝙝𝙚𝙣 𝙬𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙠 𝙖𝙗𝙤𝙪𝙩 𝙙𝙚𝙖𝙩𝙝, 𝙬𝙚 𝙜𝙚𝙩 𝙖 𝙘𝙡𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙚𝙧 𝙫𝙞𝙚𝙬 𝙤𝙛 𝙡𝙞𝙛𝙚.

The scientists asked seventy-four VAMC employees to fill in two questionnaires which asked them about the importance of various life goals, both before and after the event. The goals were categorised into intrinsic (e.g. cultivating close friendships and

personal growth) and extrinsic (e.g. career advancement and material possessions). They also asked participants questions like ‘At any time during the earthquake did you think you might die?’ to get a sense of how greatly the participants had experienced ‘mortality threat’.

The data revealed a clear pattern. After the earthquake, employees reported valuing intrinsic goals more than extrinsic ones. What’s more, the greater the sense of mortality threat they had experienced, the larger the shift towards intrinsic goals. For instance, an employee who had once been solely driven by career advancement and material wealth now found themself investing more time and energy into nurturing close relationships with family and friends. Another employee, who had previously sought validation through external praise, began to pursue creative work and personal growth for its own sake.

They show why it’s helpful to think about the most long-term time horizon of all, the end of our lives. We generate identified motivation when we can connect our goals and actions to our sense of a meaningful existence. The problem is that if you asked fifty people, ‘What does a meaningful existence look like to you?’ you’d be lucky if two of them gave you a clear answer. It’s a hard question.

And that’s where the method identified by those scientists in LA comes in. Think about the very end of your life. And use it to reappraise what matters in the here and now.

[P9]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟭:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗘𝘂𝗹𝗼𝗴𝘆 𝗠𝗲𝘁𝗵𝗼𝗱

Fortunately, you need not be caught up in a catastrophic earthquake to approach your life with the end in mind – as Leigh Penn’s obituary showed.

‘Leigh Penn, champion of at-risk youth, dies at 90,’ the account of her life read. ‘Leigh worked vehemently to close the opportunity divide.’ It vividly describes her involvement in some of the most notable causes of her time, whether leading an innovative charity that provided educational opportunities to young people from

deprived backgrounds, or helping the US Navy roll out a scheme to provide training to underserved communities across America. But even with such a high-powered career, she never lost sight of her relationships. ‘Despite being an MBA and CEO, Leigh’s favourite title was Mom,’ the obituary wrote.

It was a remarkable, ‘impactful’ life. There were just a few issues. First, Penn hadn’t actually accomplished any of the achievements listed in the obituary. Second, she hadn’t actually lived to a ripe old age of ninety. And third, she hadn’t actually died.

In fact, Penn was a student at Stanford Business School taking a famous course, ‘Lives of Consequence’. The professor, Rod Kramer, routinely assigns his students to write their own obituaries as though they have lived an ideal life – the best they can imagine – to its end.

‘The goal of this course is to change the way you think about your life and its possible impact on the world,’ the description reads. For many, including Penn, this was transformative. ‘This caused me to pause and ask, am I allocating enough time to the people I love? Or am I overly caught up in the career rat race?’ she later wrote. Reflecting on death shed light on how to live.

I’ve often used a similar approach myself. I call it the ‘eulogy method’. My iteration involves focusing not on your obituary, but on your funeral. Simply ask yourself: ‘What would I feel good about someone saying in my eulogy?’ Think about what you’d like a family member, a close friend, a distant relative, a co-worker, to say at your funeral.

This method helps us get at the question of ‘What do I value?’ from other people’s perspective. At your funeral, even your co- workers would be unlikely to say, ‘He helped us close lots of million- dollar deals.’ They’d talk about how you were as a person – your relationships, your character, your hobbies. And they’d talk about the positive impact you had on the world, not how much money you made for your employer.

Now apply what you’ve learned to your life today. What does the life you want people to remember in a few decades mean for the life you should build now?

So having started in this cheerful place, let’s bring things a little closer to home.

[P10]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟮:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗢𝗱𝘆𝘀𝘀𝗲𝘆 𝗣𝗹𝗮𝗻

In the early 1990s, Bill Burnett spent several years working at Apple. His claim to fame was always that he helped design the first Apple mouse. But in fact, Burnett worked on dozens of different projects, soon becoming an integral part of the design team. It was during this period that he began to develop a keen understanding of the intersection between good design and human need.

One day, he had an intriguing idea. Could the tools he had used to design the world’s best hardware also be applied to a human life?

Over the next few years, Burnett would come up with a new method for crafting a happier, more fulfilling existence; he called it ‘designing your life’. By applying design thinking to personal development, Burnett thought he could help people live in ways that were truer and more authentic, an approach that eventually formed the basis of the ‘Design Your Life’ course at Stanford University.

When I first discovered the Design Your Life method, it was a revelation. At the time I was a few months into my second year working as a junior doctor on obstetrics and gynaecology, and I felt a little stuck. I had a clear sense of who I was. I knew I enjoyed medicine, I loved teaching medical students, I had a small but close circle of friends and I enjoyed the routine of spending Saturday mornings at my favourite coffee shop in Cambridge’s town centre. But exactly what I wanted from life eluded me.

That’s when a friend told me about a particular exercise from the eponymous Design Your Life book. It promised to turn my vague ideas about what I wanted into a clear picture underpinned by evidence. The approach was called the ‘odyssey plan’.

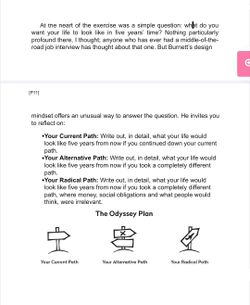

At the heart of the exercise was a simple question: what do you want your life to look like in five years’ time? Nothing particularly profound there, I thought; anyone who has ever had a middle-of-the- road job interview has thought about that one. But Burnett’s design

mindset offers an unusual way to answer the question. He invites you to reflect on:

[P12]

The point isn’t that one of these futures is actually your ‘concrete plan’ (there’s a conspicuous absence of concrete when it comes to life planning). The point is just to open your mind to the possibilities.

For some people, the first option is the one they genuinely, authentically want to go for. If that’s you, great news; you’re already aligned with your future self. But for many people, it helps you to realise that the path you’re on isn’t the path that you really want.

In my case, writing the odyssey plan made me realise that this life I was on track for – being a full-time doctor – wasn’t exciting me anymore. My current trajectory was filled with fixtures like ‘training in an anaesthesiology residency programme in the UK’. Seeing it written out made me realise that I’d set out on this path several years prior, but something in me had changed in that time – to the point that this future no longer seemed energising.

And so I changed track. The odyssey plan inspired me to focus on growing my business, instead of continuing on the path to become a medical consultant. To this day, whenever I’m at a crossroads, I repeat this exercise. By sketching out the paths ahead, you can work out which one you really want to take.

[P13]

𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗠𝗘𝗗𝗜𝗨𝗠-𝗧𝗘𝗥𝗠 𝗛𝗢𝗥𝗜𝗭𝗢𝗡

Thinking about the long-term horizon is great for figuring out what we value in the abstract. But it might feel a little nebulous. After all, if you’re in your twenties or thirties then your eulogy in (hopefully) half a century’s time might seem distant. How do you turn these abstract life plans into a coherent strategy for how to live over the next, say, year?

The answer comes from a simple method that scientists call ‘values affirmation interventions’, a scientific term for identifying your core personal values right now, and continually reflecting on them. In the last section, we sketched out some idealised life plans. With these values affirmations, we can turn them into a set of concrete ideas about what we plan to do over the next year.

These interventions are particularly powerful when you have low self-confidence in your ability to achieve what you want to in the long run. In a paper published in the journal Science, a group of psychologists used values affirmation interventions to close the gender achievement gap in physics, a subject heavily dominated by men.

Among the 400 students in the class that Akira Miyake and colleagues recruited, female students tended to perform worse than male students; they also held the belief that men were more suited to physics than women.

Miyake’s intervention was a classic values affirmation exercise.

Every student was shown a list of twelve possible values:

1. Being good at art

2. Creativity

3. Relationships with family and friends

4. Government or politics.

5. Independence

6. Learning and gaining knowledge.

7. Athletic ability

8. Belonging to a social group (such as your community, racial group or school club)

9. Music

10. Career

11. Spiritual or religious values

12. Sense of humour

Half of the students were asked to write about which three values were most important to them, and why they chose them. The other half were asked to pick the three values that were least important to them, and write about why they might be important to someone else.

This simple writing exercise had a huge effect on their mid-term exam: the intervention significantly reduced the gender gap in exam scores and improved women’s performance. And this was particularly true for women who tended to endorse the stereotype that men do better than women in physics.

Why? One possible explanation is that by affirming their values, these women were able to remember what mattered the most to them, and keep it in mind during the examination.

[P14]

⚙️ 𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙪𝙚𝙨 𝙖𝙛𝙛𝙞𝙧𝙢𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨 𝙢𝙖𝙠𝙚 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙢𝙤𝙨𝙩 𝙖𝙗𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙩 𝙞𝙙𝙚𝙖𝙡𝙨 𝙧𝙚𝙖𝙡. 𝘼𝙣𝙙 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙮 𝙗𝙤𝙤𝙨𝙩 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙛𝙞𝙙𝙚𝙣𝙘𝙚 𝙖𝙡𝙤𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙬𝙖𝙮.

So values affirmations make our most abstract ideals real. And they boost our confidence along the way. The only question is how to find these values – and how to use them.

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟯:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗲𝗹 𝗼𝗳 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲

I first got thinking about values affirmations in my penultimate year in medical school. I remember sitting in a cramped, sweltering lecture theatre on a roasting summer’s day, feeling slightly disgruntled. This

should’ve been a time for celebration: my fifth-year exams were over, and everyone in the room was due to fly out to different countries for a ‘medical elective’, a two-month placement where we got medical experience anywhere in the world. My friends Ben and Olivia and I were flying to the Children’s Surgical Centre in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, the following week.

But first, we had a few galling additional lectures for one more week, including one called ‘How to become a successful doctor’. It felt a bit much. I mean, wasn’t this what we’d been learning about for the last five years? So imagine my surprise when our tutor, Dr Lillicrap, revealed that the session wasn’t about the joys of medical admin; it was about how we could learn to define ‘success’ for ourselves.

Dr Lillicrap explained that for too many medical students, ‘success’ often defaults to academic accolades and fancy job titles. Success means much more than that, he emphasised. And then he began handing out some sheets of paper marked up with a simple exercise: the ‘wheel of life’.

The wheel of life, Dr Lillicrap explained, was a coaching framework we could use to define success for ourselves. You start by drawing a circle and slicing it up into nine segments. Around the edges of each spoke of the wheel, you write down the major areas of your life. Below are the ones that Dr Lillicrap recommended as a starting point, although you could also come up with your own. We’ve got three for Health (Body, Mind and Soul); three for Work (Mission, Money, Growth) and three for Relationships (Family, Romance, Friends).

Next, you rate how aligned you feel in each area of your life. Ask yourself: ‘To what extent do I feel like my current actions are aligned with my personal values?’ And colour in the segment accordingly – if you feel fulfilled, fill it in entirely; if you feel completely unfulfilled, leave it blank.

[P16]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟰:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝟭𝟮-𝗠𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗵 𝗖𝗲𝗹𝗲𝗯𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻

The wheel of life goes some way to explaining how to turn your values into a set of coherent objectives. It’s what inspired me to post

that first video. It also inspired at least two of my classmates to quit medicine altogether (which might not have been Dr Lillicrap’s intention).

But it still remains distant: we’re talking about abstract values rather than specific steps. That’s where our next method comes in: the ‘12-month celebration’. This is my favourite method to convert dreams into actions. The idea is simple. Imagine it’s twelve months from now and you’re having dinner with your best friend. You’re celebrating how much progress you’ve made in the areas of life that are important to you over the last year.

[P18]

𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗦𝗛𝗢𝗥𝗧-𝗧𝗘𝗥𝗠 𝗛𝗢𝗥𝗜𝗭𝗢𝗡

For some, these steps to align your goals with your life might still feel too distant. Who you are next year can still feel dauntingly distant. You need to find a way to align your behaviour now, today.

Here, our goal is to make everyday decisions that align with our deepest sense of self. This doesn’t just make us feel at ease. It is one of the most powerful drivers of feel-good productivity. In one study, Anna Sutton of the University of Waikato in New Zealand trawled through fifty-one studies made up of over 36,000 data points to explore the relationships between living authentically day-to-day and overall wellbeing.

Her findings showed not only a positive relationship between authenticity and wellbeing, but also between authenticity and what she called ‘engagement’. It amounted to a striking discovery. When people make decisions that align with their

personal values and sense of self, they aren’t just happier; they’re more engaged with the tasks before them.

So the final ingredient in alignment involves a mindset shift: from thinking about our values at the level of lifetimes and years, to thinking about our values at the level of daily choices.

The question is how. We all make decisions every day that take us away from our values. The person who values freedom, but stays in a controlling job waiting for their shares to vest. The person who values close relationships, but spends most of their time working and neglects time with family and friends. These are instances where daily decisions don’t align with what we most desire.

[P19]

⚙️ 𝙒𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙧𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩 𝙩𝙤𝙤𝙡𝙨, 𝙬𝙚 𝙘𝙖𝙣 𝙨𝙪𝙗𝙩𝙡𝙮 𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙛𝙩 𝙤𝙪𝙧𝙨𝙚𝙡𝙫𝙚𝙨 𝙗𝙖𝙘𝙠 𝙩𝙤𝙬𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙨 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙜𝙨 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙢𝙖𝙩𝙩𝙚𝙧 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙢𝙤𝙨𝙩.

But with the right tools, we can subtly shift ourselves back towards the things that matter the most, and in turn sustain our productivity (and enrich our lives) for longer.

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟱:

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗧𝗵𝗿𝗲𝗲 𝗔𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗻𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗤𝘂𝗲𝘀𝘁𝘀

My favourite way to integrate long-term values into day-to-day decisions draws upon a simple fact: short-term targets feel much easier to reach than long-term ones.

his is something psychologists have understood for decades. In one famous study, researchers asked a group of seven-to-ten-year- olds who struggled with maths to set themselves targets for the days ahead. They were split into two groups and each was given a subtly different prompt. The first was told to aim for six pages of math problems in each of the seven sessions to come; the second simply to aim for forty-two pages of problems by the end of all the sessions.

Of course, these two sets of targets are just different ways of saying the same thing – in each case, the children ended up doing all forty-two pages. And yet the effects of focusing on the immediate goal over the distant one were remarkable. The kids who were set

the ‘proximate’ goal didn’t just perform better; they performed twice as well as the other kids, correctly solving 80 per cent of problems to the 40 per cent of the other group.

What’s more, they also ended up feeling more confident – one of our most important paths to feeling good. As the organisational psychologist Tasha Eurich summarised it, ‘Proximal goals hadn’t just helped these children solve problems – they’d changed the way they looked at math.’

What does this have to do with living your values? Well, it helps overcome the distance between where we are now and where we want to be.

The idea of a 12-month celebration might feel a little daunting. I often struggle to live for a single day in line with my values, let alone a whole year. But that’s where it helps to take a leaf from the book of those mathematically minded children. Each morning, simply choose three actions for the day ahead that will move you a tiny step closer to where you want to be in a year’s time.

Personally, I have my 12-month celebration saved in a Google Doc, bookmarked on my computer’s web browser. Whenever I sit down to begin work, I open up that Google Doc and scan through it to remind myself what my 12-month celebration looks like. Then, under each of the areas of health, work and relationships, I choose one subcategory to focus on. Here’s what my three alignment quests looked like this morning:

• H – Gym session 15.30–16:30

• W – Make progress in writing Chapter 9 .

• R – Call Nani (my grandma)

This method doesn’t just work for fitness fanatics/writers/grandma fans like me. Say you’re a college student aiming to improve your grades, maintain your fitness, and strengthen your friendships. Your three alignment quests for the day could look like:

• H – Go for a 30-minute run after class.

• W – Spend an extra hour studying for tomorrow’s exam

• R – Catch up with Katherine over coffee after study session

Or you’re a working parent, juggling the demands of your job, your health and your family life. Your alignment quests could include:

• H – Take a 15-minute walk during my lunch break

• W – Complete the project proposal draft by lunchtime

• R – Cook a healthy dinner for the family and spend quality time together

The benefit of this approach is that it diminishes the terror- inducing scale of the massive 12-month objective. By focusing on the immediate, short-term steps – rather than on the whole year ahead – you turn living your values into something immediate. And achievable.

[P20]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟲:

𝗔𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗻𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗘𝘅𝗽𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁𝘀

When I first started my research into feel-good productivity a decade ago, the most powerful revelation wasn’t any one study or insight. It was a method. Everything began when I applied the scientific way of thinking I was being taught at medical school to questions of happiness, fulfilment and productivity.

So my final exercise brings us full circle, and involves learning to think about productivity like a scientist. To experiment with what brings you meaning. And use those experiments to inform the decisions you make every hour.

‘Alignment experiments’ can help you test theories about what might bring you closer to alignment in your day-to-day decision- making. It’s a process with three stages.

First, identify an area of your life where your actions feel particularly unfulfilling. The results of your eulogy method, odyssey plan and wheel of life exercises might have helped with this. But even without those exercises, you may feel a sense of misalignment in one or more areas of your life, whether your job, or your relationships, or your hobbies. Think about it – is there anywhere you feel things aren’t going well?

Think of a lawyer who has spent years climbing the corporate ladder, but who has come to realise that the long hours and high- stress environment are taking a toll on her personal life. For her, an alignment experiment might involve exploring alternative work arrangements that align better with her values.

Or imagine a college student who chose a degree based on external expectations, like pressure from family, rather than his own genuine interests. He might find himself struggling to feel engaged in classes and worrying that he’s not on the right path for his future career. In this case, an alignment experiment might involve examining alternative educational pathways.

Second, come up with your hypothesis. We’re thinking like scientists here, and that means adopting an experimental mindset. All scientific experiments have an ‘independent variable’, the one thing you change to see what effect it could have. If you were to change one – just one – independent variable in your life, what would it be? And what effect do you think it would have on your situation?

This is your hypothesis. Our demotivated lawyer’s hypothesis might be: ‘Adjusting my working hours will lead to a better balance between work and personal fulfilment.’ Our stressed-out student’s hypothesis might be: ‘Switching to a course that aligns with my personal interests and values will lead to greater satisfaction and motivation in my academic life.’

Step three is the most crucial: execute. Make a change. And as you do so, see what effect it has on your situation – and your sense of alignment.

For this to work as an experiment, it’s important that your change is localised. If you dramatically transform every sphere of your life, you won’t know what’s driving any changes in your mood and sense of alignment. So to start with, keep it small.

For our lawyer, that might mean negotiating a part-time work arrangement for three months, or delegating more draining activities to juniors to focus on energising projects – rather than immediately quitting her job. For our student, that might entail enrolling in a course in a different subject – rather than immediately trying to entirely switch degrees.

But as you do, keep track of the effects. Try keeping a log or journal of your experiences, noting any challenges, successes or insights that you gain along the way. By conducting these experiments, you give yourself the opportunity to explore an alternative path – without having to commit to it in the long term. Not yet, anyway.

These little experiments involve recognising that the journey to alignment is not one with a clear end-goal. It’s a never-ending process. As we navigate the laboratory of our lives, we must be willing to embrace experimentation – and to learn as we go.

[P21]

𝗟𝗔𝗦𝗧 𝗪𝗢𝗥𝗗: 𝗧𝗛𝗜𝗡𝗞 𝗟𝗜𝗞𝗘 𝗔 𝗣𝗥𝗢𝗗𝗨𝗖𝗧𝗜𝗩𝗜𝗧𝗬 𝗦𝗖𝗜𝗘𝗡𝗧𝗜𝗦𝗧

My apartment is a ten-minute walk from one of the biggest hospitals in London.

Some days, when I can’t focus as much as I’d like to, I wander east – through the crowds of Oxford Street’s shops and beyond the grand Victorian terraces of Marylebone – until I reach the cavernous modern entrance hall. I buy a coffee in the reception and spend a few minutes watching the doctors bustle up and down the corridors. And I think about how much has changed since that fateful Christmas Day shift; the one where I dropped the tray of medical supplies.

Watching those doctors in their scrubs – usually looking admirably less stressed than I remember the job being – I reflect on how much I’ve learned since that day. When I remember that catastrophic afternoon, my first on-call holiday in the hospital ward, I now realise that my mistake wasn’t in what I thought about productivity. It was in how I thought about it.

At the time, I was getting all the basic tactics wrong. Instead of viewing productivity in terms of what made me feel good, I was viewing it in terms of discipline: how much pressure I could pile on myself to just do more. Instead of trying to integrate play, power and people into every ward round, I was catastrophising about my sense of boredom, powerlessness and loneliness. And instead of trying to find the joy in that looming manual evacuation, I spent hours ruminating about how horrible it was going to be. (And, to be fair, it was indeed horrible.)

In the years since, everything about my life has changed. These days, I know that productivity isn’t about discipline; it’s about doing more of what makes you feel happier, less stressed, more energised. And I know that the only way to escape procrastination and burnout is to find the joy in your situation – even if you’ve just dropped 136 vials of medicinal goo all over your clothes.

But my real error wasn’t with my productivity tactics. It was with my overall strategy. I believed that if I simply learned every productivity hack and read every internet blog, I would achieve what I yearned for. It was exactly the opposite of the approach that I needed: to learn to think like a productivity scientist.

That’s why I wanted the last tool in this book to be those alignment experiments. Because in the long run, it’s only by adopting an experimental outlook that you can hope to learn the secrets of feel-good productivity. In this book, I’ve shared a few dozen experiments that worked for me. Some of them will work for you. Others won’t. And that’s ok.

Remember that this book isn’t a to-do list. It’s a philosophy – a way of creating your own personalised productivity toolkit. One that allows you to reap all of the amazing rewards of feeling good, every day, and in the long term. And one that involves approaching your daily projects and tasks in the spirit of experimentation.

So, I urge you: try as much as you can, figure out what works, and discard the rest. Ask yourself of every new approach: what effect does this have on my mood? On my energy? On my productivity? Don’t rote-learn your way to feel-good productivity. Experiment your way.

Ultimately, it’s only by continually evaluating what works for you that you’ll work out how to feel better in the long run. Productivity is an evolving field, and you’re evolving too. There’s still so much to discover. Yet as you apply these principles in your life, you’ll uncover the insights, strategies and techniques that work best for you. They may well be more useful than mine, especially because they came from within you.

⚙️ 𝗗𝗼𝗻’𝘁 𝗿𝗼𝘁𝗲-𝗹𝗲𝗮𝗿𝗻 𝘆𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝘄𝗮𝘆 𝘁𝗼 𝗳𝗲𝗲𝗹-𝗴𝗼𝗼𝗱 𝗽𝗿𝗼𝗱𝘂𝗰𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗶𝘁𝘆. 𝗘𝘅𝗽𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝘆𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝘄𝗮𝘆

So enjoy the process. And as you go, remember that this process isn’t about striving for perfection. It’s about strategically stumbling your way to what works. Learning from your failures and celebrating

your successes. Transforming your work from a drain on your resources to a source of energy.

It’s a difficult mindset to adopt. But when you’ve adopted it, everything changes. If you can tap in to what makes you feel most energised and alive, you can get anywhere. And you can enjoy the journey too.

I can’t wait to see where your adventure takes you next.

By undefined

22 notes ・ 0 views

English

Elementary