Dec 22, 2024

CH3: Feel Good Productivity

[P1]

𝗖𝗛𝗔𝗣𝗧𝗘𝗥 𝟯: 𝗣𝗘𝗢𝗣𝗟𝗘

Have you ever noticed that after hanging out or working with certain people, you feel like you’re ready to take on the world? These are the word people who uplift your spirits and fill you with energy. You want to be around them.

On the other hand, you’ve also probably come across people who leave you feeling drained and exhausted after every interaction. It’s as if they cast a shadow over your mood and motivation. People learn to avoid them like the plague. And they learn fast.

A friend of mine refers to the latter group as ‘energy vampires’. They suck the lifeblood out of a social situation leaving everybody in the vicinity exhausted. When I first heard of the term ‘energy vampire’, I thought it was a bit too harsh and a bit too fantastical. But she had a point.

Scientists have long been aware of what they call ‘relational energy’: the fact that our interactions with others can have a profound effect on our mood. In a study in 2003, psychology professors Rob Cross, Wayne Baker and Andrew Parker came up with the concept of an ‘energy map’. They worked with consultants and managers in a few giant firms to establish who worked with whom, and the impact that any given person had on other people’s energy levels. Their discovery? That there was a remarkable amount of agreement about who was an energiser (and who was a drainer) even at the level of large organisations. Some people are just a total nightmare to be around.

In the years since, relational energy has become one of the buzziest concepts in organisational science. Defined as ‘the positive

feeling and sense of increased resourcefulness experienced as a direct result of an interaction with someone else’, relational energy was the subject of only eight studies in 2010; by 2018 the number was closer to eighty.

So relational energy provides us with our final energiser: people. As that 2003 study showed, people can enhance our mood and make us more productive. But this isn’t a given. It requires deep thought about how we connect with each other. In this chapter, we’ll explore various ways we can surround ourselves with people to feel more energised, and to do more of the things that matter.

[P2]

𝗙𝗜𝗡𝗗 𝗬𝗢𝗨𝗥 𝗦𝗖𝗘𝗡𝗘

Our first insight into the feel-good effects of people comes from the world of 1970s glam rock.

It was the beginning of a new decade, and Brian Eno looked to be on his way to a life of contented mediocrity. A recent graduate of the Winchester School of Art, he had been involved in a few avant-garde music projects in recent years – drumming in the odd art rock band and recording the odd song on his battered tape recorder – but nothing had quite taken off. He seemed set for a life as a well-liked but peripheral player in London’s rock world.

And then, one day in 1971, a chance encounter with a local musician changed everything. Eno was waiting for his train when he bumped into an acquaintance, the saxophonist Andy Mackay, who invited him to a local club where he was playing. When they arrived at the gig, the atmosphere was electric: the crowd was buzzing with excitement and the energy in the room gripped Eno. Later, he would say of the chance meeting with Mackay, ‘If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform, or missed that train, or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.’

Instead, Eno found himself in the midst of a vibrant and exciting music scene. In the weeks that followed, he talked to the people he met about music – and found himself producing the best art of his life. With Mackay, he would found the influential glam rock band Roxy Music – and eventually become one of the most significant musicians and producers of the last century.

Years later, Eno would reflect on the importance of that unique musical community in launching his career. He noticed that all the most innovative and ground-breaking musicians of his time were not working in isolation; they were part of a larger scene of artists, producers and fans who were all pushing each other to explore new sounds and ideas. Eno had discovered the genius of the collective scene. Or, as he called it, scenius.

I’ve experienced the effects of scenius first-hand. One thing I didn’t like about medical school was the sense of competition. Everyone was trying to get the highest grade, the academic prize, the best slot in the residency programme. Some took this competitive mindset a little far. One guy I knew would take out multiple copies of the same textbook from the library so that others couldn’t use it. Such environments encourage people to see their lives as a zero-sum game: for them to win, others have to lose.

But there’s another way to think about your relationship with your peers, I eventually learned. Medical school wasn’t a competition. We were all part of the same scene. By understanding that fact, we were able to access a wealth of support that we would never have alone.

[P3]

⚗️ 𝙀𝙓𝙋𝙀𝙍𝙄𝙈𝙀𝙉𝙏 𝟭:𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝘾𝙤𝙢𝙧𝙖𝙙𝙚 𝙈𝙞𝙣𝙙𝙨𝙚𝙩

How can we build this sense of scenius into our day-to-day lives? The answer begins with a subtle shift: reappraising what we mean by teamwork.

When someone says the word ‘teamwork’, we tend to imagine a set of behaviours – splitting up work fairly, or maybe helping someone out when they get stuck. That’s part of it, certainly. But there’s another way of understanding teamwork: less as something to do, and more as a way of thinking.

🔗 𝙏𝙚𝙖𝙢𝙬𝙤𝙧𝙠 𝙞𝙨 𝙖𝙨 𝙢𝙪𝙘𝙝 𝙖 𝙥𝙨𝙮𝙘𝙝𝙤𝙡𝙤𝙜𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙡 𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙖𝙨 𝙖 𝙬𝙖𝙮 𝙤𝙛 𝙙𝙞𝙫𝙞𝙙𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙪𝙥 𝙩𝙖𝙨𝙠𝙨.

This is the suggestion of Stanford professors Gregory Walton and Priyanka Carr, anyway. They’ve argued that teamwork is as much a psychological state as a way of dividing up tasks. In a study published in 2014, they divided thirty-five participants into groups of three to five. After the experimentees had met and introduced themselves, they were taken into individual rooms. The scientists then gave each participant a puzzle and told them they could take as much or as little time to solve it as they needed.

After working on their puzzles for several minutes, all participants received a handwritten tip on how to solve them. All the tips were the same (and were genuinely helpful). But there was one crucial difference. When some participants were given the tip, they were told it had been written for them by the scientist running the study. Others were told it had been written for them by one of the fellow participants, who they’d met earlier.

This small difference had a significant impact on how the participants felt about the experiment. Those who were told that the tip was from the scientists were more likely to feel like they were working completely separately from the participants they met. When asked to describe what they did in the study, some replied, ‘I did an individual puzzle while other people did the same puzzle.’ They were working in parallel, not together.

In contrast, people who were told that the tip was from a fellow student were more likely to feel as if they were on a team with the others; they felt like they were ‘trying to collaborate with an invisible partner to solve the problem by sending each other tips’. When asked how they felt during the study, some participants wrote, ‘I would feel obligated to work hard on the puzzle so as not to disappoint other people.’ They were no longer working in parallel. They were working together.

This subtle change of mindset had a remarkable effect. Participants in the ‘together’ group ended up working on the puzzle for 48 per cent longer. They had developed what I call a comrade mindset. And they were doing better as a result.

This subtle difference – between ‘working in parallel’ and ‘working together’ – might seem small. But it hints at the first tool we can use to harness the energising effects of people. Even if we’re on our own in undertaking a task, we can convince ourselves that we’re part of a team – and do so with remarkable ease.

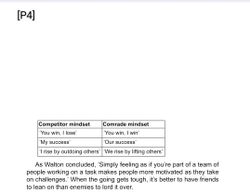

The trick is to deliberately think about the people you’re working alongside as part of your team. Look at the following list. What would it take to move your focus away from the column on the left, and towards the column on the right? What would it look like if these people weren’t competitors, but comrades. If you’re an employee, could you recruit people to work with you and rely on each other for moral support? If you’re a student, can you share your notes or find ways to revise in groups?

[P5]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟮 : 𝗙𝗶𝗻𝗱 𝗦𝘆𝗻𝗰𝗵𝗿𝗼𝗻𝗶𝗰𝗶𝘁𝘆

There are moments when it can be difficult to find people to collaborate with, of course. Sometimes, it can be hard to force yourself to think about people working on the other side of the campus (let alone world) as part of the same team. Sometimes, our peers can simply be rather annoying.

In these moments, we can draw upon a second tool, one I first came across via a confoundingly clever study by three academics at Ryerson University in Canada. In a 2017 paper, these academics brought together a group of 100 students to investigate the science of teamwork. After being divided into groups of six, the students were given headphones and asked to tap their hand on the table to a musical beat. Some groups of six were briefly all given the same musical beat – so they were tapping in synchrony. In other groups of six, two subgroups of three were given the same music to tap to. Finally, some people were given six completely different soundtracks, so there was no synchrony at all.

After that, the headphones were taken away, and replaced by some new props. Each participant was now given ten tokens to dole out, which they were told would be converted into real money later. Who did they want to give them to?

What the scientists were interested in testing was the sense of camaraderie between the participants who were ‘in sync’. And they found that the level of musical synchronicity changed everything. When participants spent time tapping fingers in synchrony with the trio, they wanted to dole out money to the trio. But if two of these trios tapped in sync – forming a group of six for a few minutes – the members were more likely to donate to all six.

🔗 𝙎𝙮𝙣𝙘𝙝𝙧𝙤𝙣𝙞𝙘𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙢𝙖𝙠𝙚𝙨 𝙪𝙨 𝙬𝙖𝙣𝙩 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙚𝙡𝙥 𝙤𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙨. 𝘼𝙣𝙙 𝙞𝙩 𝙢𝙖𝙠𝙚𝙨 𝙪𝙨 𝙬𝙖𝙣𝙩 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙚𝙡𝙥 𝙤𝙪𝙧𝙨𝙚𝙡𝙫𝙚𝙨.

What does any of this have to do with the feel-good effects of other people? Well, it tells us something powerful about how to create a sense of teamwork. When we work in synchrony with other people, we tend to be more productive. Synchronicity makes us want to help others. And it makes us want to help ourselves.

The implications are simple: if we want to harness the feel-good effects of people, try to find people with whom to work in sync – even if you aren’t actively collaborating on the same task. In the course of writing this book, I often attended the London Writers’ Salon, which runs a free, remote co-working group called Writers’ Hour. Every weekday, four times a day, a few hundred writers (and some non- writers) assemble on a Zoom video call. The facilitator spends five minutes sharing a motivational message and asking participants to post in the online chat what their intention for their writing session is going to be. Then, for fifty minutes, everyone minimises their Zoom window, and works away at their computer.

I continue to find these sync sessions incredibly helpful for staying energised. Even though we’re all working on different things, working in tandem with others has huge effects on my ability to focus, and helps me feel better too.

[P6]

𝗙𝗘𝗘𝗟 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗛𝗘𝗟𝗣𝗘𝗥’𝗦 𝗛𝗜𝗚𝗛

I noticed something else in those virtual writing sessions. With time, I got to know the other people in my group; soon, we’d start messaging each other for support on Zoom. And that would eventually lead me to another dimension of relational energy: the effect of giving and receiving help.

It’s an effect that Allan Luks understands better than anyone. As the head of Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City, Luks was responsible for a network of thousands of volunteers and staff members who were dedicated to improving the lives of young people in New York City. The work could be difficult, and often upsetting. The organisation matched adult mentors with children and teenagers, who were often in the throes of huge family crises – ranging from imprisonment to addiction to suicide. Luks was passionate about the importance of mentorship and the impact it could have on young people. But it was tough.

And yet as his months at Big Brothers Big Sisters turned to years, Luks started to notice something odd. Yes, the volunteers were sometimes left exhausted or upset by what they experienced. But more often, they left even the trickiest mentoring sessions highly energised. Luks began to realise that the act of giving could transform not only the lives of the people being helped, but also the lives of the volunteers themselves.

Intrigued by this phenomenon, over the next few years he interviewed thousands of volunteers who had experience helping others. They all said they chose to do this work because, in part, it made them feel great. He found that 95 per cent of the volunteers

reported feeling happier, more fulfilled and more energised as a result of their service.

Why might that be? Luks’s research showed that when we help others, our brains release a flood of chemicals that create a natural high. Feel-good hormones like oxytocin surge through our bodies, creating a wave of positive energy that can last for hours – even days – after the helping has ended.

Luks realised that the ‘helper’s high’ wasn’t just a feeling. It was a powerful tool for growth, social change and, I would add, feel-good productivity. It’s the second way we can use the feel-good effects of other people to do more of what matters to us.

[P7]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧𝟯 : 𝗥𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗼𝗺 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗞𝗶𝗻𝗱𝗻𝗲𝘀𝘀.

When I worked as a doctor, whenever I had a few minutes spare between seeing patients, I’d get up to make myself a cup of tea.

On one level, this was a selfish act; I am, arguably, Britain’s leading tea connoisseur. But I also had half an eye on the wider team. On my way to the kitchen, I’d poke my head into the nurses’ office and ask if anyone would like me to make them a cup too. This tiny act seemed to have a weirdly significant effect on team morale. I vividly remember offering Julie, one of the senior nurses, a cup of tea at the height of the Covid pandemic; she looked like I’d just offered her a winning lottery ticket. All for a lowly teabag, some hot water and a splash of milk (crucially, in that order).

These random acts of kindness offer the first way to integrate the helper’s high into our day-to-day lives. By stopping what you’re doing and offering help to people at random, you can boost your endorphin levels and help yourself work harder.

Tea is not the only such act of kindness, of course. You can integrate kindnesses into every day, whatever your situation. Say you work in an office. Have you noticed that someone around you looks bored, or a little burned out? Why not take them out for lunch instead of having a sandwich at your desk?

Or perhaps you’re in the supermarket and someone behind you looks stressed – maybe they have young children. Why not let them go in front of you in the queue?

Or say someone has done you an act of kindness, even a little one; they’ve taken a task that was on your to-do list at a busy time. Why not write them a personalised thank-you note?

There are any number of these random acts of kindness. Making a colleague a drink. Writing a friend a thank-you note. Offering a stranger your place in line. All subtle. But all subtly transformative too.

[P8]

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟰:

𝗔𝘀𝗸 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗛𝗲𝗹𝗽 𝗳𝗿𝗼𝗺 𝗢𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿𝘀

The helper’s high also shows us that asking for help from others can actually be a gift to them, rather than the burden we usually assume it will be.

This was an epiphany experienced by the young Benjamin Franklin – the polymathic founding father of the United States, who, over his 84-year life, would philosophise on the nature of statecraft, found Philadelphia’s first fire department, and sign the US Declaration of Independence. In 1737, though, all that was far ahead of him. Franklin was running for re-election in the Pennsylvania Assembly. A rival legislator was saying some unfavourable things about him. He had completely opposing views to Franklin, and they had a strained – often frosty – relationship.

Franklin desperately needed to stop this man’s propaganda campaign against him; it was at risk of blowing up his bid for re- election. But how could he win over someone who didn’t agree with him on anything? The answer, he explained in his autobiography, involved borrowing a book. ‘Having heard that he had in his library a certain very scarce and curious book, I wrote a note to him, expressing my desire of perusing that book, and requesting he would do me the favour of lending it to me for a few days,’ Franklin wrote. To Franklin’s surprise, his nemesis sent it immediately. When

Franklin returned the book, he included a note expressing how much he enjoyed it.

Surprisingly, this had a profound impact on their relationship. ‘When we next met in the House, he spoke to me (which he had never done before), and with great civility,’ Franklin wrote. ‘And he ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.’

This seemingly small act – borrowing a book – had a significant effect on Franklin’s opponent and on Franklin himself. The man was so surprised by the gesture that he began to see Franklin in a new light. He couldn’t reconcile the fact that he had helped someone he disagreed with. As a result, the man’s attitude towards Franklin began to change for the better.

This concept is today known as the ‘Benjamin Franklin effect’. It suggests that when we ask someone for help, it’s likely to make them think better of us. It’s the flipside of the transformative effects of helping others: we can ask others to help us, which will help them feel better, too.

It’s a pity, then, that most of us are bad at asking for help. We might need a crucial piece of information from a colleague, but instead of ‘bothering’ them, we try to figure it out ourselves, wasting time in the process. Or we might be struggling with a particular problem in class, but find ourselves not wanting to ask for help from the person next to us, or even the teacher, for fear of looking stupid.

So how can we learn to ask for help – in a way that warms people to us, rather than alienates them? Well, there are a few ways. First, we need to get over our reluctance to ask. The easiest way to do this is by simply adopting a maxim: people are more eager to help than you think. We have by now repeatedly seen how energising it can be to make others smile, to teach, and to mentor. Even so, a lot of us underestimate how willing other people are to help us. According to the academics Francis Flynn and Vanessa Bohns, people tend to underestimate the likelihood that other people will agree to help us by up to 50 per cent.

Second, frame the request in the right way. In particular, do your best to ask for help in person. Asking virtually makes everything more difficult. In a 2017 study, Bohns found that ‘help-seekers assumed making a request via email would be equally as effective as making a request in person; in actuality, asking for help in-person was approximately thirty-four times more effective’.

Finally, make sure you’re using the right language. Avoid using negative phrases like ‘I feel really bad for asking you this…’ and avoid turning it into a transaction by saying things like ‘If you help me, I’ll do this for you.’ Instead, emphasise the positive reasons for why you’re going to that specific person for advice: ‘I saw your work on X, Y, Z and it really had an impact on me. I would love to hear how you did A, B, C.’ By emphasising the positive aspects of the person you admire, they’ll think you genuinely value their opinion – and be more likely to help you.

This last insight is key. When framed correctly, asking for help makes the person you’re asking feel as good as the help makes you feel. If you want to harness the power of the Benjamin Franklin effect, you should do everything you can to ask without any sense of a quid pro quo.

[P9]

𝗢𝗩𝗘𝗥𝗖𝗢𝗠𝗠𝗨𝗡𝗜𝗖𝗔𝗧𝗘

When I first launched my business, the thing I struggled with most was the need for communication. To be precise, quite how much of it was necessary.

I knew that sharing information was important, obviously. What I hadn’t realised was how much I needed to communicate. I eventually realised – usually thanks to helpful pointers from my long-suffering team – that my fears about being too overbearing had made me not communicate enough. I wasn’t giving the positive or negative feedback that most of my team members really wanted. This is a common phenomenon. We’re much more likely to underestimate how much communication we need to do than overestimate it.

🔗 𝙒𝙝𝙚𝙣 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙠 𝙮𝙤𝙪’𝙫𝙚 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙪𝙣𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙥𝙡𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙮, 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙖𝙡𝙢𝙤𝙨𝙩 𝙘𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙖𝙞𝙣𝙡𝙮 𝙝𝙖𝙫𝙚𝙣’𝙩

So where most books about bringing people together focus on communication, here I want to focus on the power of over- communication. When you think you’ve communicated plenty, you almost certainly haven’t. Different team members might interpret the shared information in different ways or have different levels of context or understanding. Overcommunicating means deliberately going beyond the minimum you think is necessary, and consequently ending up sharing exactly the right amount. But how?

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟱:

𝗢𝘃𝗲𝗿𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝗰𝗮𝘁𝗲 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗚𝗼𝗼𝗱

A Swedish proverb says: ‘A shared joy is a double joy; a shared sorrow is a half sorrow.’ When one person shares good news with another, both people are happy. And when one person shares something sad with another, the act of sharing takes some of the sadness away.

The first tactic for over communicating the good, then, is to share positive news – and to react to positive news in an energising way. This helps both the sharer and the responder. For the sharer, the simple act of sharing positive news increases positive emotions and psychological wellbeing. For the responder, expressing pride and happiness in the other person’s accomplishments fuels a positive interaction and bolsters the relationship.

In psychology, this form of self-reinforcing positive interaction is called capitalisation. One paper on the subject characterises capitalisation as involving two components. The first part involves someone (the sharer) trying to connect with someone else through a positive event and the positive emotions associated with it. For example, you might go to a friend and say, ‘Hey, I finally got that salary raise I was looking for!’ In the second part, the good-news recipient reacts in a positive way, with enthusiasm and excitement. So they might say, ‘Oh wow, that’s so great. I know you’ve been working really hard for that raise!’

Simple, perhaps. But not necessarily straightforward. Because, according to the University of California psychology professor Shelly Gable, there are myriad ways you can respond to good news – and not all of them are as positive. We can think of these as falling on two axes. First, whether your response is active or passive, and second, whether your response is constructive or destructive.

Suppose your flatmate returns home one day and tells you that they’ve been offered a job that they’ve been working hard for. Here are how these four different responses would look like:

[P11]

Gable and her colleagues found that responding to good news in an active-constructive way makes the sharer of the good news happier, and makes the relationship stronger. Indeed, in a 2006 study, researchers videotaped seventy-nine couples who were dating to examine how they discussed good news and bad news with each other. It turns out that how participants responded to their partners’ good news was the strongest predictor of how long they’d stay together and how happy they were in those relationships.

So being able to celebrate people’s wins matters. And the best way to do so is to adopt an active-constructive approach to all good news.

Fortunately, this is something we can learn. The first step is to feel and show your delight and joy for the other person’s good news. Try phrases like ‘That’s such wonderful news’ and ‘I couldn’t be happier for you!’

Next, recall to the sharer of good news how you’ve actively witnessed the process that led to the good news. Perhaps you’ve seen how hard they’ve worked to prepare for that job interview, the weeks they studied for the qualifying exam, how much they wanted that outcome.

And above all, show your optimism for how this good news might shape their future (without overburdening them with high expectations). If someone’s just landed a dream job, share how excited you are for the opportunities ahead of them. If someone’s just quit a mundane job to start their own business, share how excited you are for them about their future adventures.

[P12]

🔗 𝙊𝙫𝙚𝙧𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙪𝙣𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙬𝙤𝙣’𝙩 𝙟𝙪𝙨𝙩 𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙥𝙞𝙧𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙢. 𝙄𝙩 𝙬𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙥𝙞𝙧𝙚 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙩𝙤𝙤.

At every turn, try to make your overcommunication about the good as positive and as uplifting as possible. Overcommunication won’t just inspire them. It will inspire you too.

⚗️ 𝗘𝗫𝗣𝗘𝗥𝗜𝗠𝗘𝗡𝗧 𝟲:

𝗢𝘃𝗲𝗿𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝗰𝗮𝘁𝗲 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗡𝗼𝘁-𝗦𝗼-𝗚𝗼𝗼𝗱

In order to really harness the feel-good effects of other people, we don’t just need to communicate good news, though. We need to learn to communicate bad news too. Unfortunately, we’re not always very good at that.

The problem is that we humans are just too good at lying. It’s not just that we lie every day; we lie every hour. According to a 2002 study conducted by University of Massachusetts psychologist Robert Feldman, 60 per cent of people lie at least once in an average ten- minute conversation.

Not all lies are created equal, of course. Most lies are trivial and told with good intentions – like telling a friend that you love his new trainers when they’re not your style, or reassuring your mother that the roast chicken is absolutely not dry.

But there’s a downside. Lying – even lying with good intentions – has a physiological effect. Lying is associated with the activation of the limbic system, the same area of the brain that initiates the fight- or-flight response. When we’re honest, this area of the brain shows minimal activity; when telling a lie, it lights up like a fireworks display.

The reason for all this lying is that honesty often feels like a lose– lose situation. We lose if we’re too honest because we come across like a jerk. But we also lose if we’re not honest because we feel resentful about being stuck in a situation that we’re not ok with. This is tricky for anyone who has adopted the maxim of overcommunication: we need to communicate the bad stuff without lying needlessly. Is there a way?

According to author and CEO coach Kim Scott, the solution is not to be honest but candid. In her book Radical Candor, Scott writes that being radically candid is about caring personally (that is, genuinely caring about the person you’re speaking to) while also

directly challenging the issue at hand. Being radically candid doesn’t mean making the issue personal, it doesn’t mean assuming you know best, and it doesn’t mean saying whatever pops into your head. It does mean sharing your opinions directly, not talking badly about people behind their backs, and giving your co-workers insight into what’s going on in your head.

Choosing the word ‘candid’ over ‘honest’ has some benefits. Being honest implies that you know the truth. It often has a moral connotation to it that can put people off (the memory of my school friend James insulting my card tricks with a flippant ‘I’m just being honest, mate’ haunts me to this day). When we say, ‘Let me be honest with you,’ it’s almost as if we’re saying,

‘This is the truth, and I’m going to tell you what it is.’ But when it comes to interpersonal dynamics, the truth is often unclear. Your line manager might feel like a drainer to you, but it might not be true that this person is an objectively bad manager. For all we know, they could be a good manager for other people, or maybe they’re going through something in their personal lives that’s affecting them at work.

In contrast, being candid doesn’t assume that we know the truth. The spirit of being candid is more like: ‘Here’s what I think. Can you hear me out or help me out? We can do it together.’

So how can we all learn to craft a culture of candid feedback, one that delivers negative feedback without ruining anyone’s day? Well, there are a few steps to follow. First, root your analysis in objective, non-judgemental terms. ‘I noticed you cut Hermione off a few times in that meeting’ is much more effective than ‘You are incredibly rude.’ Similarly, telling people ‘You are wrong’ or ‘You are incompetent’ is going to make that person feel attacked and defensive – it’s too subjective (not to mention a little rude, too). Just stick to the facts.

Second, focus on the tangible results of what’s gone wrong. Again, subjectivity is your enemy. So simply highlight, factually, the consequence of what you observed. For example, ‘I noticed that after you interrupted Ron in the meeting the discussion died down a bit. That’s a real shame because I would have really liked to hear what other people have to say.’

Finally, turn your attention away from the problem and towards the solution. Provide alternatives of what you’d like to see happen. For example, ‘Next time, please wait until people are finished speaking before sharing your thoughts’ or ‘Next time, maybe you could ask people questions to show that you’re interested in their view but might not agree with them. I feel like asking questions might get a better reaction from them and maybe lead to collaboration.’ Offering alternatives focuses the discussion on possible solutions to the problem and helps the other person avoid feeling personally criticised.

These three steps are a simple way to make overcommunication of unpleasant news a little easier. They all hint at the notion that it’s possible to bring people together and make them feel good, even when you’re delivering bad news. Not a lie in sight.

By undefined

13 notes ・ 0 views

English

Elementary