Oct 17, 2023

Atomic Habit #3

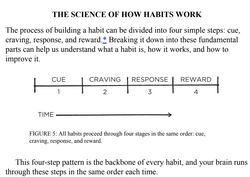

First, there is the cue. The cue triggers your brain to initiate a behavior. It is a bit of information that predicts a reward. Our prehistoric ancestors were paying attention to cues that signaled the location of primary rewards like food, water, and sex. Today, we spend most of our time learning cues

that predict secondary rewards like money and fame, power and status, praise and approval, love and friendship, or a sense of personal satisfaction. (Of course, these pursuits also indirectly improve our odds of survival and reproduction, which is the deeper motive behind everything we do.) Your mind is continuously analyzing your internal and external environment for hints of where rewards are located. Because the cue is the first indication that we’re close to a reward, it naturally leads to a craving.

Cravings are the second step, and they are the motivational force behind every habit. Without some level of motivation or desire—without craving a change—we have no reason to act. What you crave is not the habit itself but the change in state it delivers. You do not crave smoking a cigarette, you

crave the feeling of relief it provides. You are not motivated by brushing your teeth but rather by the feeling of a clean mouth. You do not want to turn on the television, you want to be entertained. Every craving is linked to a desire to change your internal state. This is an important point that we will discuss in detail later. Cravings differ from person to person. In theory, any piece of information could trigger a craving, but in practice, people are not motivated by the same cues. For a gambler, the sound of slot machines can be a potent trigger that sparks an intense wave of desire. For someone who rarely gambles, the jingles and chimes of the casino are just background noise. Cues are meaningless until they are interpreted. The thoughts, feelings, and emotions of the observer are what transform a cue into a craving. The third step is the response. The response is the actual habit you

perform, which can take the form of a thought or an action. Whether a response occurs depends on how motivated you are and how much friction is associated with the behavior. If a particular action requires more physical or mental effort than you are willing to expend, then you won’t do it. Your response also depends on your ability. It sounds simple, but a habit can occur only if you are capable of doing it. If you want to dunk a basketball but can’t jump high enough to reach the hoop, well, you’re out of luck.

Finally, the response delivers a reward. Rewards are the end goal of every habit. The cue is about noticing the reward. The craving is about wanting the reward. The response is about obtaining the reward. We chase rewards because they serve two purposes: (1) they satisfy us and (2) they teach us.

The first purpose of rewards is to satisfy your craving. Yes, rewards provide benefits on their own. Food and water deliver the energy you need to survive. Getting a promotion brings more money and respect. Getting in shape improves your health and your dating prospects. But the more immediate benefit is that rewards satisfy your craving to eat or to gain status or to win approval. At least for a moment, rewards deliver contentment and relief from craving. Second, rewards teach us which actions are worth remembering in the future. Your brain is a reward detector. As you go about your life, your sensory nervous system is continuously monitoring which actions satisfy your desires and deliver pleasure. Feelings of pleasure and disappointment

are part of the feedback mechanism that helps your brain distinguish useful actions from useless ones. Rewards close the feedback loop and complete the habit cycle. If a behavior is insufficient in any of the four stages, it will not become a

habit. Eliminate the cue and your habit will never start.

Reduce the craving and you won’t experience enough motivation to act. Make the behavior difficult and you won’t be able to do it. And if the reward fails to satisfy your desire, then you’ll have no reason to do it again in the future. Without the first three steps, a behavior will not occur. Without all four, a behavior will not be repeated.

THE HABIT LOOP

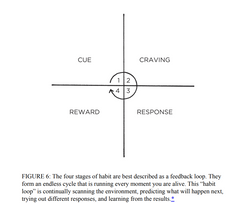

In summary, the cue triggers a craving, which motivates a response, which provides a reward, which satisfies the craving and, ultimately, becomes associated with the cue. Together, these four steps form a neurological feedback loop—cue, craving, response, reward; cue, craving, response, reward—that ultimately allows you to create automatic habits. This cycle is known as the habit loop.

This four-step process is not something that happens occasionally, but rather it is an endless feedback loop that is running and active during every moment you are alive—even now. The brain is continually scanning the environment, predicting what will happen next, trying out different responses, and learning from the results. The entire process is completed in a split second, and we use it again and again without realizing everything that has been packed into the previous moment.

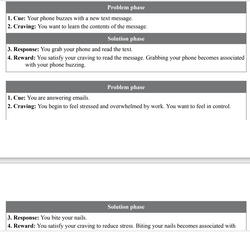

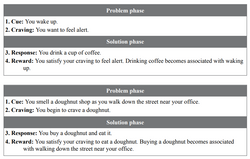

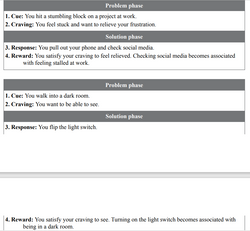

We can split these four steps into two phases: the problem phase and the solution phase. The problem phase includes the cue and the craving, and it is when you realize that something needs to change. The solution phase includes the response and the reward, and it is when you take action and achieve the change you desire.

All behavior is driven by the desire to solve a problem. Sometimes the problem is that you notice something good and you want to obtain it. Sometimes the problem is that you are experiencing pain and you want to relieve it. Either way, the purpose of every habit is to solve the problems you face.

In the table on the following page, you can see a few examples of what this looks like in real life. Imagine walking into a dark room and flipping on the light switch. You have performed this simple habit so many times that it occurs without thinking. You proceed through all four stages in the fraction of a second. The urge to act strikes you without thinking.

By the time we become adults, we rarely notice the habits that are running our lives. Most of us never give a second thought to the fact that we tie the same shoe first each morning, or unplug the toaster after each use, or always change into comfortable clothes after getting home from work. After decades of mental programming, we automatically slip into these patterns of thinking and acting.

THE FOUR LAWS OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE

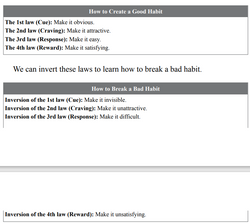

In the following chapters, we will see time and again how the four stages of cue, craving, response, and reward influence nearly everything we do each day. But before we do that, we need to transform these four steps into a practical framework that we can use to design good habits and eliminate bad ones.

I refer to this framework as the Four Laws of Behavior Change, and it provides a simple set of rules for creating good habits and breaking bad ones. You can think of each law as a lever that influences human behavior. When the levers are in the right positions, creating good habits is effortless. When they are in the wrong positions, it is nearly impossible.

It would be irresponsible for me to claim that these four laws are an

exhaustive framework for changing any human behavior, but I think they’re

close. As you will soon see, the Four Laws of Behavior Change apply to

nearly every field, from sports to politics, art to medicine, comedy to

management. These laws can be used no matter what challenge you are

facing. There is no need for completely different strategies for each habit.

Whenever you want to change your behavior, you can simply ask yourself:

1. How can I make it obvious?

2. How can I make it attractive?

3. How can I make it easy?

4. How can I make it satisfying?

If you have ever wondered, “Why don’t I do what I say I’m going to do? Why don’t I lose the weight or stop smoking or save for retirement or start that side business? Why do I say something is important but never seem to make time for it?”

The answers to those questions can be found somewhere

in these four laws. The key to creating good habits and breaking bad ones is to understand these fundamental laws and how to alter them to your specifications. Every goal is doomed to fail if it goes against the grain of human nature.

Your habits are shaped by the systems in your life. In the chapters that follow, we will discuss these laws one by one and show how you can use them to create a system in which good habits emerge naturally and bad habits wither away.

Chapter Summary

1. A habit is a behavior that has been repeated enough times to become automatic.

2. The ultimate purpose of habits is to solve the problems of life with as little energy and effort as possible.

3. Any habit can be broken down into a feedback loop that involves four steps: cue, craving, response, and reward.

4. The Four Laws of Behavior Change are a simple set of rules we can use to build better habits. They are (1) make it obvious, (2) make it attractive, (3) make it easy, and (4) make it satisfying

THE FIRST LAW: MAKE IT OBVIOUS

The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

THE PSYCHOLOGIST GARY Klein once told me a story about a woman who attended a family gathering. She had spent years working as a paramedic and, upon arriving at the event, took one look at her father-in-law and got

very concerned. “I don’t like the way you look,” she said.

Her father-in-law, who was feeling perfectly fine, jokingly replied, “Well, I don’t like your looks, either.” “No,” she insisted. “You need to go to the hospital now.”

A few hours later, the man was undergoing lifesaving surgery after an examination had revealed that he had a blockage to a major artery and was at immediate risk of a heart attack. Without his daughter-in-law’s intuition,

he could have died. What did the paramedic see? How did she predict his impending heart attack?

When major arteries are obstructed, the body focuses on sending blood to critical organs and away from peripheral locations near the surface of the skin. The result is a change in the pattern of distribution of blood in the face. After many years of working with people with heart failure, the woman had unknowingly developed the ability to recognize this pattern on sight. She couldn’t explain what it was that she noticed in her father-in-law’s face, but she knew something was wrong.

Similar stories exist in other fields. For example, military analysts can identify which blip on a radar screen is an enemy missile and which one is a plane from their own fleet even though they are traveling at the same speed, flying at the same altitude, and look identical on radar in nearly every respect. During the Gulf War, Lieutenant Commander Michael Riley saved an entire battleship when he ordered a missile shot down—despite the fact that it looked exactly like the battleship’s own planes on radar. He made the right call, but even his superior officers couldn’t explain how he did it.

Museum curators have been known to discern the difference between an authentic piece of art and an expertly produced counterfeit even though they can’t tell you precisely which details tipped them off. Experienced radiologists can look at a brain scan and predict the area where a stroke will develop before any obvious signs are visible to the untrained eye. I’ve even heard of hairdressers noticing whether a client is pregnant based only on the feel of her hair.

The human brain is a prediction machine. It is continuously taking in your surroundings and analyzing the information it comes across. Whenever you experience something repeatedly—like a paramedic seeing the face of a heart attack patient or a military analyst seeing a missile on a

radar screen—your brain begins noticing what is important, sorting through the details and highlighting the relevant cues, and cataloging that information for future use.

With enough practice, you can pick up on the cues that predict certain outcomes without consciously thinking about it. Automatically, your brain encodes the lessons learned through experience. We can’t always explain what it is we are learning, but learning is happening all along the way, and your ability to notice the relevant cues in a given situation is the foundation

for every habit you have.

We underestimate how much our brains and bodies can do without thinking. You do not tell your hair to grow, your heart to pump, your lungs to breathe, or your stomach to digest. And yet your body handles all this and more on autopilot. You are much more than your conscious self.

Consider hunger. How do you know when you’re hungry? You don’t necessarily have to see a cookie on the counter to realize that it is time to eat. Appetite and hunger are governed nonconsciously. Your body has a variety of feedback loops that gradually alert you when it is time to eat

again and that track what is going on around you and within you. Cravings can arise thanks to hormones and chemicals circulating through your body. Suddenly, you’re hungry even though you’re not quite sure what tipped you off.

This is one of the most surprising insights about our habits: you don’t need to be aware of the cue for a habit to begin. You can notice an opportunity and take action without dedicating conscious attention to it. This is what makes habits useful. It’s also what makes them dangerous. As habits form, your actions come under the direction of your automatic and nonconscious mind. You fall into old patterns before you realize what’s happening. Unless someone points it out, you may not notice that you cover your mouth with your hand whenever you laugh, that you apologize before asking a question, or that you have a habit of finishing other people’s sentences. And the more you

repeat these patterns, the less likely you become to question what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.

I once heard of a retail clerk who was instructed to cut up empty gift cards after customers had used up the balance on the card. One day, the clerk cashed out a few customers in a row who purchased with gift cards. When the next person walked up, the clerk swiped the customer’s actual credit card, picked up the scissors, and then cut it in half—entirely on autopilot—before looking up at the stunned customer and realizing what had just happened.

Another woman I came across in my research was a former preschool teacher who had switched to a corporate job. Even though she was now working with adults, her old habits would kick in and she kept asking coworkers if they had washed their hands after going to the bathroom. I also

found the story of a man who had spent years working as a lifeguard and would occasionally yell “Walk!” whenever he saw a child running.

Over time, the cues that spark our habits become so common that they are essentially invisible: the treats on the kitchen counter, the remote control next to the couch, the phone in our pocket. Our responses to these cues are so deeply encoded that it may feel like the urge to act comes from nowhere.

For this reason, we must begin the process of behavior change with awareness. Before we can effectively build new habits, we need to get a handle on our current ones. This can be more challenging than it sounds because once a habit is firmly rooted in your life, it is mostly nonconscious and automatic. If a habit remains mindless, you can’t expect to improve it. As the psychologist Carl Jung said, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

THE HABITS SCORECARD

The Japanese railway system is regarded as one of the best in the world. If you ever find yourself riding a train in Tokyo, you’ll notice that the conductors have a peculiar habit. As each operator runs the train, they proceed through a ritual of pointing at different objects and calling out commands. When the train approaches a signal, the operator will point at it and say, “Signal is green.” As the train pulls into and out of each station, the operator will point at the speedometer and call out the exact speed. When it’s time to leave, the operator will point at the timetable and state the time. Out on the platform, other employees are performing similar actions. Before each train departs, staff members will point along the edge of the platform and declare, “All clear!” Every detail is identified, pointed at, and named aloud.*

This process, known as Pointing-and-Calling, is a safety system designed to reduce mistakes. It seems silly, but it works incredibly well. Pointing-and-Calling reduces errors by up to 85 percent and cuts accidents by 30 percent. The MTA subway system in New York City adopted a modified version that is “point-only,” and “within two years of implementation, incidents of incorrectly berthed subways fell 57 percent.”

Pointing-and-Calling is so effective because it raises the level of

awareness from a nonconscious habit to a more conscious level. Because the train operators must use their eyes, hands, mouth, and ears, they are more likely to notice problems before something goes wrong.

My wife does something similar. Whenever we are preparing to walk out the door for a trip, she verbally calls out the most essential items in her packing list. “I’ve got my keys. I’ve got my wallet. I’ve got my glasses. I’ve got my husband.”

The more automatic a behavior becomes, the less likely we are to consciously think about it. And when we’ve done something a thousand times before, we begin to overlook things. We assume that the next time will be just like the last. We’re so used to doing what we’ve always done that we don’t stop to question whether it’s the right thing to do at all. Many of our failures in performance are largely attributable to a lack of self-awareness

One of our greatest challenges in changing habits is maintaining awareness of what we are actually doing. This helps explain why the consequences of bad habits can sneak up on us. We need a “point-and-call” system for our personal lives. That’s the origin of the Habits Scorecard, which is a simple exercise you can use to become more aware of your behavior. To create your own, make a list of your daily habits.

Here’s a sample of where your list might start:

Wake up

Turn off alarm

Check my phone

Go to the bathroom

Weigh myself

Take a shower

Brush my teeth

Floss my teeth

Put on deodorant

Hang up towel to dry

Get dressed

Make a cup of tea

. . . and so on.

Once you have a full list, look at each behavior, and ask yourself, “Is this a good habit, a bad habit, or a neutral habit?” If it is a good habit, write “+” next to it. If it is a bad habit, write “–”. If it is a neutral habit, write “=”.

For example, the list above might look like this:

Wake up =

Turn off alarm =

Check my phone –

Go to the bathroom =

Weigh myself +

Take a shower +

Brush my teeth +

Floss my teeth +

Put on deodorant +

Hang up towel to dry =

Get dressed =

Make a cup of tea +

The marks you give to a particular habit will depend on your situation and your goals. For someone who is trying to lose weight, eating a bagel with peanut butter every morning might be a bad habit. For someone who is trying to bulk up and add muscle, the same behavior might be a good habit.

It all depends on what you’re working toward.*

Scoring your habits can be a bit more complex for another reason as well. The labels “good habit” and “bad habit” are slightly inaccurate. There are no good habits or bad habits. There are only effective habits. That is, effective at solving problems. All habits serve you in some way—even the

bad ones—which is why you repeat them. For this exercise, categorize your habits by how they will benefit you in the long run.

Generally speaking, good habits will have net positive outcomes. Bad habits have net negative outcomes. Smoking a cigarette may reduce stress right now (that’s how it’s

serving you), but it’s not a healthy long-term behavior.

If you’re still having trouble determining how to rate a particular habit, here is a question I like to use: “Does this behavior help me become the type of person I wish to be? Does this habit cast a vote for or against my desired identity?” Habits that reinforce your desired identity are usually good. Habits that conflict with your desired identity are usually bad.

As you create your Habits Scorecard, there is no need to change anything at first. The goal is to simply notice what is actually going on. Observe your thoughts and actions without judgment or internal criticism. Don’t blame yourself for your faults. Don’t praise yourself for your successes. If you eat a chocolate bar every morning, acknowledge it, almost as if you were watching someone else. Oh, how interesting that they would do such a thing. If you binge-eat, simply notice that you are eating more calories than you should. If you waste time online, notice that you are spending your life in a way that you do not want to.

The first step to changing bad habits is to be on the lookout for them. If you feel like you need extra help, then you can try Pointing-and-Calling in your own life. Say out loud the action that you are thinking of taking and what the outcome will be. If you want to cut back on your junk food habit but notice yourself grabbing another cookie, say out loud, “I’m about to eat this cookie, but I don’t need it. Eating it will cause me to gain weight and hurt my health.”

Hearing your bad habits spoken aloud makes the consequences seem more real. It adds weight to the action rather than letting yourself mindlessly slip into an old routine. This approach is useful even if you’re simply trying to remember a task on your to-do list. Just saying out loud, “Tomorrow, I need to go to the post office after lunch,” increases the odds that you’ll actually do it. You’re getting yourself to acknowledge the need for action—and that can make all the difference.

The process of behavior change always starts with awareness. Strategies like Pointing-and-Calling and the Habits Scorecard are focused on getting you to recognize your habits and acknowledge the cues that trigger them, which makes it possible to respond in a way that benefits you.

Chapter Summary

With enough practice, your brain will pick up on the cues that predict certain outcomes without consciously thinking about it.

Once our habits become automatic, we stop paying attention to what we are doing.

The process of behavior change always starts with awareness. You need to be aware of your habits before you can change them.

Pointing-and-Calling raises your level of awareness from a

nonconscious habit to a more conscious level by verbalizing your

actions.

The Habits Scorecard is a simple exercise you can use to become more aware of your behavior

By undefined

25 notes ・ 103 views

English

Intermediate